February 24, 2020

Advancing Advance Care Plans through Medicare: It’s Time to Move

American culture and politics make little room for honest discussions about death and dying. Healthcare thought leader Ian Morrison is fond of saying, “In Scotland, death is imminent. In Canada, death is inevitable. In California, death is optional.” So it seems.

It’s a well-known fact that if you want to clear a room of US politicians just say, “Let’s talk about death.” Our policy makers don’t have the lexicon to discuss death in the context of social policy without the very real possibility of a chorus of banshees screaming “Death Panels.”

Yet, as we will argue, there is a role for government, one it has neglected. According to the Centers for Disease Control, there were 2,839,205 deaths in 2018 for residents of the United States,[1] or as an elected official might think of them: “ex-voters.” So why should the government care?

Of the 2.8 million deaths, just over 2 million occurred in persons sixty-five years of age or older.[2] That means roughly 70 percent of US deaths occurred in persons who are very likely to be on Medicare or some other form of government-funded health insurance. A portion of those dying under the age of 65 also carry government-funded health insurance.

All Americans should establish advance care plans (ACPs) to document their goals of care preferences in the event they have a health crisis and can’t speak – whether it leads to death or not. Why? What good can an ACP do? Research shows that people with an ACP are 3x more likely to have their wishes followed. Without an ACP, cancer patients are 7x more likely to have mechanical ventilation and 8x more likely to undergo attempts at resuscitation at the end of life. Nursing home patients without an ACP have more hospitalizations, are less satisfied with their care and have 33% higher costs of care.

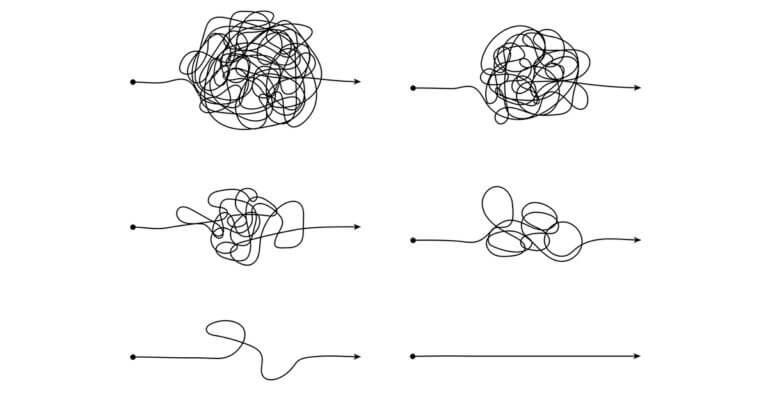

In other words, ACPs can improve outcomes, quality, patient safety, clarity around wishes and, by reducing confusion and chaos as well as unwanted treatments, reduce cost. Despite decades of public policy statements about creating ACPs, only about a third of Americans have done so. Since little intentional standardization has occurred around ACPs, if someone has one there’s little chance it will be accessible in a health emergency.

The facts above highlight some of the compelling moral, clinical and fiscal reasons why Medicare should both make it easier for individual Americans to complete ACPs, and for frontline clinicians to find and follow them. Before we dig into policy, however, we’d like to share our personal ACP stories.

The Authors and Advance Care Plans

We had the good fortune to first meet each other in the mid-1980s through our wives, who were best friends in college. Kerry had just begun his lifelong healthcare career as a junior analyst in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. He rose through the ranks to become the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Budget and finally Acting Administrator of the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) in 2007. More on that in a moment.

When we met, Dave had just completed a Public Policy degree and was working as a U.S. Presidential Management Intern at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. His professional experience was in finance, economic development and transportation. Finance led him into investment banking which led him into healthcare.

In 2007 when Kerry was CMS Administrator, a relative died from heart failure. What was shocking to Kerry was that this relative’s medical team replaced his relative’s hip even though he was incapacitated and near death. Kerry knew that this relative would never have agreed to this surgery if he had been asked or if he’d had an ACP that was accessible in his medical record.

While running CMS, Kerry and HHS Secretary Mike Leavitt worked to develop policies to prevent this type of wasteful and unnecessary care on vulnerable and elderly patients. Unfortunately the Administration changed before they could improve Medicare’s ACP rules and best practices. A sense of unfinished business has haunted Kerry ever since.

Happily, in his post-government career Kerry met Jeff Zucker, CEO of MyDirectives, creators of a global digital advance care planning platform. For the last ten years, Kerry has worked pro-bono with Jeff to continue to advance the cause of advance care planning.

Now to Dave’s story.

After a long and successful investment banking career, Dave launched 4sight Health as a thought leadership platform in 2014. The next year, the BMO-Harris Private Bank asked him to assemble a program on end-of-life decision-making for presentation to the Bank’s high-net-worth clients.

After making sure the Bank actually wanted to talk about death with its clients, Dave dug into the task with gusto and gave over twenty presentations at Bank-hosted events throughout the US. The program included an article, a slide presentation, a “readiness checklist” and suggestions for initiating end-of-life conversations with loved ones. Dave’s first book, Market vs. Medicine, incorporated this material into its chapter 7, “It’s the Customer, Stupid!”

Fast-forward to January 2020 when Kerry described his advocacy work for advance care planning to Dave and introduced him to Jeff Zucker. After listening to Dave regale him with the story of his work on end-of-life decision-making, Jeff simply asked Dave whether he had his own ACP. That was embarrassing. The cobbler had no shoes. Dave subsequently completed an ACP through the MyDirectives website and committed to working with Kerry and Jeff to raise awareness amongst policy leaders and business decision-makers.

That’s how we got here, and it’s time to move. It’s maddening that more Americans don’t have ACPs. It’s even more maddening that providers either can’t find or ignore them when they do exist. This is definitely a problem that technology can help solve.

Let’s return to Medicare and explore ways the Agency can encourage widespread adoption of ACPs.

The Painful Road to Advance Care Plans

The most publicized end-of-life care cases involved three young women, none of whom had clear advance care plans. Karen Ann Quinlan was 21 in 1975 when she fell into a persistent vegetative state after ingesting valium and alcohol. Nancy Cruzan was 25 in 1983 when she fell into a persistent vegetative state after being ejected from her car into a water-filled ditch. Terri Schiavo was 26 in 1990 when lack of oxygen from a cardiac arrest pushed her into a persistent vegetative state.

Each of these cases created enormous heartache for the families involved and required adjudication through the American legal system. The Quinlan case centered on the ethics of ending life support. The Quinlan family won the ability to disconnect Karen from oxygen support in a decision by the New Jersey Supreme Court, but the Quinlan family continued tube-feeding and hydration. Karen lived another nine years.

The Cruzan case, decided by the US Supreme Court, held that a competent person’s wishes in refusing further treatment are Constitutional. It further held that those speaking for a noncompetent person must present “clear and convincing evidence” of that individual’s end-of-life care preferences. The Cruzan family gathered sufficient evidence to meet the court-mandated threshold to cease treatment. Caregivers disconnected Nancy’s feeding tube on December 14, 1990. She died 12 days later.

The Schiavo case centered on whether her husband or her parents had the right to make Terri’s end-of-life care decisions. The Schiavo case commanded the nation’s attention and became a political football. A long, torturous jurisprudential and legislative battle decided who spoke for Terri — in favor of her husband. At his request, caregivers removed Terri’s feeding tube on March 18, 2005. She died on March 31, 2005, fifteen years after going into cardiac arrest.

These three women were the involuntary trailblazers who gave life and force to advance care planning. They established the constitutional right for a competent individual to refuse treatment, established a standard for the same when one can’t speak for oneself, and affirmed that wishes and evidence of those wishes can be communicated by a third party. Having said all of that, none of us know what their wishes truly were.

These cases silently and eloquently make the argument that ACPs are just as important for the young as the not so young. Indeed, the third-leading cause of death is accidental injury, which disproportionately afflicts the young. In other words, everyone 18+ needs an ACP. Then society – the private and public sectors — need to coordinate efforts to ensure everyone (1) has a plan, (2) that each person’s plan is accessible in a crisis, (3) that medical professionals respect and honor the wishes of the people they treat.

Dying with Medicare

Medicare is far and away the biggest payer at the end of life. Medicare will soon pass Social Security to become the federal government’s largest social program. In 2018 there were 59.9 million enrollees at an expenditure of $740.6 billion[4] (or roughly the GDP of Turkey.) Baby boomers are now aging into Medicare at a rate of 10,000 people per day.

From its inception in 1965, Medicare has reimbursed providers for the costs of medical treatments. In the words of its enabling legislation, Medicare will pay for services that are “…reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or treatment of illness or injury or to improve the functioning of a malformed body member…”

The important point here is that Medicare was designed to pay for treatments, not for preventive or end-of-life care. Congress didn’t add hospice benefits to Medicare until 1982, and then did it through, of all things, the “Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act.” Preventive care benefits came even later.

A recent study estimates that Medicare’s end-of-life spending constitutes 13-25 percent of all benefit costs.[5] That suggests that in 2018, Medicare spent between $96 billion and $185 billion on care services during the last year of life. Beyond its cost, end-of-life care can be a nightmare for unprepared Medicare patients and their families.

In a recent Washington Post op-ed[6], Dr. Geoffrey Hosta makes the case that some care given in acute situations amounts to torture. He describes the case of a near-death dementia patient with a high fever. Her well-meaning family, not knowing her wishes, agreed to a full treatment regimen. This essentially condemned her to a painful, highly medicalized death in a hospital. Her treatment included having her ribs broken in a resuscitation attempt.

American healthcare has a built-in bias for aggressive treatment. The system pays doctors and hospitals more to do more, even when aggressive treatments do not align with patient desire. Even to the point, as illustrated above, of forcibly treating those who lack the ability to direct their own care.

The clear solution to avoiding unwanted care is for individuals to clearly express their treatment preferences in advance within a secure, accessible, trustworthy instrument that can direct care when those individuals can no longer speak for themselves. The means to achieve this desirable objective is through digital ACPs.

The Digital Advantage

At this point, we’ve probably lost half of our readers thinking “I can’t afford a lawyer, and who needs another piece of paper floating around my already cluttered life.” Stick with us another moment or two, because advance care planning has gone digital and doesn’t require an attorney.

Smart phones are ubiquitous in America. We can order food, transportation, merchandise, and innumerable other products and services from our phones. Not only can consumers learn algebra, play Sudoku or watch cat videos on their phones, but they can now create digital ACPs.

Platforms such as ADVault’s MyDirectives have moved ACPs out of lawyers’ offices and musty filing cabinets into smartphones. In minutes on a free app, individuals can articulate their goals of care and treatment preferences. They can designate the person or persons who have authority to speak on their behalf if they can’t communicate. The best apps use published security protocols that allow linking to most electronic health records. Some apps, like MyDirectives or MIDEO, offer the ability to augment the ACP with a personalized video, eliminating any authenticity concerns.

An old adage suggests that the best time to fix the roof is when the sun is shining. This wisdom applies to completing ACPs. The best time to create, update and share an ACP is well in advance (pun intended!) of any apparent need. This guarantees that the System will have access to individual care preferences, not automatically default to pursuing “all necessary means” to prolong life.

How the Government Can Help

So what is the government’s role? We believe strongly that:

- Only patients, healthcare agents and providers should know the content of an individual ACP.

- The consumer should always be able to decide who can see their goals of care and treatment wishes.

- Consumers should have the ability to update their ACP at no cost to them, at any time.

The government nor any other insurer, should never know the contents of an individual’s plan and wishes. The government can, however, make it easier for Americans to create and implement their ACPs.

To be fair, Medicare did add advance care planning as a covered Medicare service in 2016. The service is part of the annual “wellness check.” Alternatively, ACP also can occur as a separately billable service when offered outside of the wellness check. Medicare compensates physicians for explaining ACP and its use, as well as for familiarizing the patients or their surrogates with the application process. At this point physicians can charge Medicare for providing this service without any evidence of completing an ACO, or even evidence that one exists and can be found in the electronic health record.

We believe shifting from a process measure to an outcome measure will help millions of Americans live with more confidence that they will have their voices heard in their care.

Medicare’s heart is in the right place, but unfortunately the operating realities of its ACP procedures resembles the 1960s nightmare of long-lost papers and overstuffed filing cabinets. There’s a better, more modern digital solution.

Every year 3.65 million people become eligible for Medicare (10,000/day x 365 days). Enrollment is simple, and done online. As a vestige of a long-disappeared past, the Social Security Administration is the enrollment agent for Medicare.[7] Imagine this: the online enrollment process for all Medicare services would engage new enrollees in the following line of questioning.

- “Do you have an advance care plan or advance directive? Who speaks for you in a medical emergency if you can’t communicate?”

- If the answer is yes and the senior names someone, then enrollment continues. NOTE: the more private payers, employers and providers ask people to create and update their ACPs, the more likely the answer will be yes.

- If the answer is “no,” the program can present new enrollees with links to Medicare-approved digital ACP vendors, some of whom offer their services for free.

- The enrollee can create a digital ACP or navigate away from the page.

- Government involvement in ACP ends at that point. Medicare never knows what individuals decide.

Here’s the kicker for Medicare and other governmental payers: enlightened, accessible, care that is based on a person’s values is better for patients, and it costs everyone less. If end-of-life care costs represents 13-25 percent of Medicare’s total costs, reducing these costs by just 5 percentage points would save roughly $37 billion annually. This is not a small number. Moreover, the value of the dignity returned to Medicare patients who avoid unwanted, valueless and often harmful care is priceless.

American as Apple Pie

Dating back to the nation’s revolutionary beginnings, there is a core American belief in the right of individuals to control their destiny. Nowhere is this fundamental American belief put more to the test than in end-of-life care. More often than not, the US healthcare system cannot discover or overrides individual care preferences at the end of life.

This is un-American and unacceptable.

There is significant political disagreement on healthcare. Advocating for widespread use of ACPs, however, is not controversial. In 2012, Cornell University hosted a debate[8] between conservative Senator Rick Santorum and liberal Governor (Dr.) Howard Dean on the role of government in a free society. In a spirited 90-minute exchange, the only policy on which Santorum and Dean could agree was governmental support for the MyDirectives approach to digital ACPs: neutral approach, free to consumers, consumer-owned and easy to use, update and share, and always accessible.

It is incumbent upon all Americans to make their wishes known to guarantee that they will receive the treatment they want when they’re unable to speak.

Do it for yourself. Do it for those you love. Do it for professional caregivers. Do it as your part of a consumer-empowerment revolution to have a stronger voice in your care.

Government, most notably Medicare, can make it easier for individuals to create ACPs and easier for providers to follow patients’ wishes. Government of, by and for the people requires nothing less.

Sources

- “Mortality in the United States, 2018.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 30, 2020.

- Kochanek, Murphy, Xu, Arias. Deaths: Final data for 2017. Centers for Disease Control, National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 68 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

- Neither Kerry Weems nor David Johnson receive compensation from ADVault or any company for their advocacy with respect to advance care planning.

- “Trustees Reports (Current and Prior).” CMS, April 2019.

- Duncan, Ian, Tamim Ahmed, Henry Dove, and Terri L Maxwell. “Medicare Cost at End of Life.” The American journal of hospice & palliative care. SAGE Publications, March 18, 2019.

- Hosta, Geoffrey. “Opinion | Doctors Are Torturing Dementia Patients at the End of Their Life. And It’s Totally Unnecessary.” The Washington Post. WP Company, November 28, 2019.

- Medicare pays Social Security over $2 billion a year for enrollment, maintenance of the rolls, and other services. In an excellent example of what the government does for cost allocation, the payment is not related to effort or the value that Medicare may derive from Social Security. See the Medicare Trustees Report, source 4 above.

- “Howard Dean and Rick Santorum Debate Role of Government.” CornellCast, October 18, 2012.

Make your Advance Care Plan now, using either of these free services: MyDirectives or Medio.

Co-author:

Kerry Weems is Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Mycroft Bioanalytics, an early-stage company specializing in licensing of genetic and clinical intellectual property. He is also Executive Chairman of the Value-Based Healthcare Investors Alliance (VBHIA), an alliance of payers, providers, and others devoted to “moving the needle” on value-based health care. Formerly, he was Chief Executive Officer of TwinMed, as well as holding leadership roles at General Dynamics and Vangent.

Kerry Weems is Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Mycroft Bioanalytics, an early-stage company specializing in licensing of genetic and clinical intellectual property. He is also Executive Chairman of the Value-Based Healthcare Investors Alliance (VBHIA), an alliance of payers, providers, and others devoted to “moving the needle” on value-based health care. Formerly, he was Chief Executive Officer of TwinMed, as well as holding leadership roles at General Dynamics and Vangent.

Prior to his private sector career, Mr. Weems served 28 years with the Federal Government in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, rising to Deputy Assistant Secretary for Budget. Nominated by President George W. Bush, he held the position of Acting Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services from 2007 to 2009. He is a two-time recipient of the Presidential Rank Award, the highest honor in the civilian service. He holds an MBA and bachelor’s degree in philosophy and business administration.