August 1, 2023

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do: Moving Behavioral Health Into the 21st Century

If you like antiques you should love our behavioral healthcare system. Despite the development of advanced medications, it still largely operates as it did in the 19th century. People receive treatment within a parallel system divorced from general healthcare. Efforts at prevention are rudimentary where they do exist. Success is still measured in hospital releases, not recoveries.

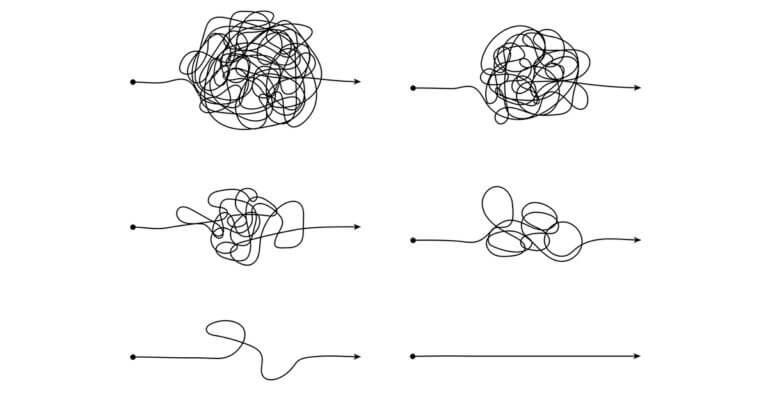

Behavioral healthcare needs a revolution if both the current level of disease and the costs are to be brought under control. America needs the following three radical changes in behavioral health to rescue our system, or it will ravage our economy and create a widening gap in our society:

- Collection and publication of data.

- Integration of behavioral and general healthcare.

- Establishing prevention programs.

Collection and Publication of Data

Behavioral health is awash in data and has precious little information. In general, behavioral health providers do not measure their work on the basis of outcomes. In an insightful article in The New Yorker in November 2004, Dr. Atul Gawande wrote about the problem of wanting excellence in healthcare, and only being able to find standard care. [1]

In the course of the article, he describes cystic fibrosis (CF) care. For CF, there is a nationwide registry of programs that collects information on patient life expectancy and other care outcomes. One provider, LeRoy Matthews, discovered a series of improvements in care that dramatically increased life for those suffering from CF.

Due to Matthews’ breakthrough work and its documentation, CF care nationwide was revolutionized. Life expectancy for CF patients soared. This improvement became possible because providers could see how their outcomes measured up against better-performing treatment programs.

When applied appropriately, there is power in data and data sharing. For this reason, behavioral health needs to replicate CF nationwide data-sharing model. Only by knowing which programs are achieving better than average success on key desired outcomes can the rest of the field begin to improve.

Today there is no collective data demonstrating which behavioral health programs are best at getting individuals back to work and/or living a fulfilling life. Providers must record the time required to bring people from a state of dysfunction to full recovery. With this information, behavioral healthcare, like CF, can standardize care delivery and improve care outcomes.

Integration of Behavioral and General Healthcare

Since the origins of modern American medicine in the 1800s, American healthcare has separated behavioral and physical healthcare services. Sanatoriums catered to the mentally impaired, hospitals treated the sick and injured. These separate worlds of care rarely integrated with one another.

In present-day America, this care divide still exists. These separated treatment systems and the fragmented care they deliver leads to higher overall care costs, sicker populations and limited accountability for care outcomes. Despite some efforts at integration, the current system provides neither recovery nor wellness.

There is no overall health and well-being without adequate behavioral health. Studies have shown repeatedly the benefits of interconnecting behavioral and physical health. There have been some efforts to recognize the value of integrating physical and behavioral healthcare services. This generally occurs by offering general healthcare services in behavioral health settings. Imagine only getting care for your strep throat by going to your behavioral health provider.

Worse, behavioral health is directly linked to some major chronic diseases such as heart failure and COPD. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) observes the following in its “Healthy People” post,

Mental health and physical health are closely connected. Mental health plays a major role in people’s ability to maintain good physical health. Mental illnesses, such as depression and anxiety, affect people’s ability to participate in health-promoting behaviors. In turn, problems with physical health, such as chronic diseases, can have a serious impact on mental health and decrease a person’s ability to participate in treatment and recovery. [2]

This “disconnection” between physical and mental health services impairs overall health and increases care costs significantly.

There is good documentation of links between behavioral health problems and chronic diseases such as COPD and heart failure; however, these expenses are not attributed as linked behavioral health costs. They are simply added to all other incremental costs, which together drive up the aggregate costs of those morbidities.

In addition, studies [3] indicate a significant portion of patient complaints to their primary care providers have no recognized etiology or treatment course. Many of these “mystery complaints” have their origin in behavioral health conditions that providers rarely address because payment requires additional time and documentation. It’s simply not financially viable to provide the care. As a consequence, these mental health conditions often get reimbursed as basic primary care concerns or don’t get reimbursed at all.

Behavioral health providers’ exemption from expectations for specific results has had an upside and a downside. On the upside: They have been able to achieve continuous funding simply on the basis of providing services. This has resulted in the emergence of a very large mental health industry.

On the downside: Separating physical and mental health assessment and service delivery encourages the general public to see behavioral health issues as different, and possibly of greater concern, than other diseases. Seeking care for mental health conditions raises questions about the customer’s relative fitness, not the adequacy of their care. This is simply wrong.

This negative perception can delay care for emerging problems and exacerbate the illness. No caregiver suggests waiting to treat heart disease or cancer. To do so would be unthinkable. The same logic applies to behavioral health conditions. Earlier diagnosis and treatment are always better. This requires making behavioral healthcare a part of every primary care visit. Clinicians must incorporate behavioral health as a routine part of their care regimens. Treatment for physical and mental health conditions must become one and inseparable.

Establishing Prevention Programs

Prevention is a crucial part of general health programs. Vaccinations, screenings, checkups and improving sanitation all are part of an organized effort to prevent the onset of illness or injury. By contrast, there are only rudimentary efforts at prevention in behavioral health.

In the last decade programs which address Recovery After First Psychotic Episode (RA1SE) have achieved major improvement in diseases akin to Schizophrenia. While there is a need for these programs to compare procedures and results, more widespread use of these proven therapies is essential.

Overall, the behavioral health field has been slow to adopt the life-saving approaches these RA1SE programs have developed. Prevention, as practiced in RA1SE programs, is the most potent and effective strategy for reducing the incidence of these mental health problems and associated costs.

In 2008 The National Council began distributing Mental Health First Aid (MHFA). [4] Originally developed in Australia, this program was a laudable effort to encourage grassroots attention to behavioral health. Unfortunately, researchers have not been able to find significant improvements in support for people with behavioral health problems as a result of the MHFA training. [5]

Nevertheless, this effort recognizes the importance of prevention. It is extremely difficult to find other prevention initiatives in behavioral health. Efforts to establish mental health care in schools have had mixed results. They generally focus on providing emergency care services, not prevention.

Even so, it is essential to expand elementary and secondary-school curricula to teach young people the importance of good behavioral health as well as how to achieve and maintain it. This bold step requires educating all teachers and caregivers to recognize and address emergent behavioral health problems — before they become debilitating.

The Call to Action

The status quo for behavioral health is broken. Recent changes in the behavioral health system, triggered at least in part by the desire to reduce gun violence, are useful but represent the status quo approach of separating physical and mental healthcare service provision.

An outcomes-based, measurement-based approach works, and there are integrated approaches that have shown excellent results. This approach has the major benefits of somewhat reducing behavioral health costs and, in addition, reduces the overall cost of medical care.

Every dollar reduction due to behavioral health reduces medical care costs by two-thirds.

If we want to create behavioral health and not just behavioral healthcare, we have to make revolutionary changes in our systems of care. We must gather comprehensive data, integrate behavioral healthcare within general healthcare and develop prevention programs to make radical changes in behavioral healthcare delivery.

This isn’t the 1800s. We no longer travel by stagecoach. It’s beyond time to elevate and modernize behavioral health services in the U.S.

Sources

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2004/12/06/the-bell-curve

- Morgan AJ, Ross A, Reavley NJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Mental Health First Aid training: Effects on knowledge, stigma, and helping behaviour. PLoS One. 2018 May 31;13

- J Psychosom Res. 1997 Mar;42(3):245-52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00292-9.

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14694702/

- https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/get-involved/mental-health-first-aid/