September 30, 2015

Doc-Fix Legislation: Medicare Makes Physicians an “Offer They Can’t Refuse”

David Johnson and Nathan Bays-Doc-Fix Legislation: Medicare Makes Physicians an “Offer They Can’t Refuse”

After years of temporary fixes and short-term extensions, the U.S. Congress repealed Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate (“SGR”) legislation last April. The SGR formula has shaped physician payment mechanics and politics since its creation in 1997. In SGR’s place, Congress has substituted payment methodologies that shift physician reimbursement dramatically toward value-based delivery.

While physicians fought hard to repeal SGR, few appreciate the magnitude of payment reform embedded in the new legislation.

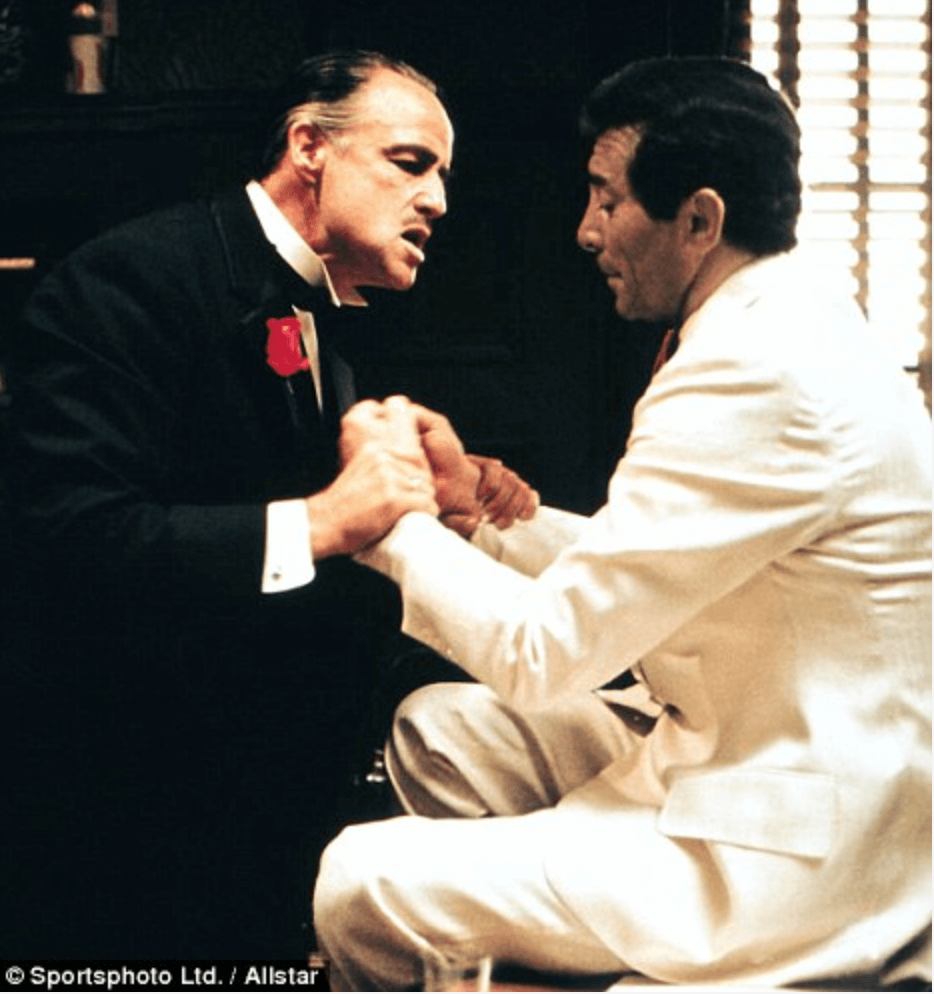

The new physician payment program reminds us of the famous scene in “The Godfather” where fading crooner Johnny Fontane (think Frank Sinatra) asks the Godfather to secure a part for him in an upcoming blockbuster movie (think Maggio in “From Here to Eternity”).

Johnny had just finished singing for his only daughter’s wedding, so the Godfather was feeling generous. He assures Johnny he’ll have the part within a month.

Given the director’s intransigence, Johnny wonders how that can happen. The Godfather famously says, “I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse.” Of course Johnny gets the part.

Rather than intimidating physicians Godfather-style, Medicare is using financial incentives to achieve better, more consistent and cost-effective care delivery. Medicare’s “offer” to physicians, however, is as direct as the Godfather’s – assume performance risk or watch your reimbursement income plummet.

Fuzzy Math

Congress embedded the SGR in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 to control the growth of Medicare payments to physicians. The SGR formula calculated the difference between actual and targeted expenditures. If actual expenditures exceeded the target, Medicare would implement a “negative payment” adjustment the following year to capture the previous year’s excess payment.

Congress embedded the SGR in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 to control the growth of Medicare payments to physicians. The SGR formula calculated the difference between actual and targeted expenditures. If actual expenditures exceeded the target, Medicare would implement a “negative payment” adjustment the following year to capture the previous year’s excess payment.

In essence, the SGR formula required doctors to “repay” any excess reimbursement through lower payments the next year. Easier said than done.

2002 was the first year actual expenditures exceeded the targets. Advocates for physicians railed against lower physician payments in 2003. With the political heat on, Congress passed a short-term “patch” to override the SGR and avoid reducing physician payments. This was the first of seventeen legislative “doc fixes”.

With each “doc fix”, the gap between Medicare’s targeted physician payment and its actual physician payment expanded. For budgetary purposes, Congress continued to recognize the SGR’s phantom savings. This budgetary sleight-of-hand made SGR repeal more costly. Passing new legistlation would require Congress to “write off” the substantial difference between targeted and actual physician payments since 2002.

With little trust between parties and Obamacare’s white-hot politics, Congress could not muster the votes necessary to resolve SGR’s obvious flaws. Fuzzy math ruled the day

Medicare-Congressional Resolution?

Coming into 2015, the SGR formula required a 21.2% percent reduction in physician payment this fiscal year. Continuing SGR’s fuzzy math was becoming untenable. Fiscal reality necessitated legislative innovation.

A bi-partisian Congressional initiative developed a pathway to eliminate the SGR and implement major payment reform. This initiative incorporated value-based payments for physicians. After much wrangling and deal-cutting, the House and Senate passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015.

The new legislation repealed the SGR, expands a popular children’s health program and changes how Medicare will pay doctors beginning in 2019. No more fuzzy math. The law recognizes and accounts for the $141.9 billion loss generated under SGR. President Obama signed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 into law on April 16th.

“Déjà Vu All Over Again”[1]

While debating the Affordable Care Act, then Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi (in)famously stated that “we have to pass the bill so you can find out what’s in it.” In the wake of SGR repeal, many have a sense of déjà vu. While happy to wave goodbye to the SGR, physicians are slowly realizing that fee-for-service Medicare is phasing out and a new, somewhat unknown payment scheme will replace it.

Beginning in 2019, Medicare will offer physicians a choice of two payment model tracks: the Merit Incentive Based Payment System (“MIPS”) track or the Alternative Payment Model (“APM”) track. Here’s how they work:

Merit Incentive Payment System (MIPS): physicians will continue to receive fee-for-service payments, but will be subject to publically-available quality and performance metrics that impact their final reimbursement. MIPS physicians will receive an annual score between 0-100 and payment based on their composite scores. CMS also will publish physician scores on its website, enabling peer comparisons on quality and performance metrics.

At a surface level, Medicare is offering physicians a choice between performance-based, fee-for-service payment with public reporting and reimbursement adjustments (MIPS) or phased value-based payment (APM). Over time, however, payment incentives force physcians into the APM.

An “Offer” Physicians Can’t Refuse

Under APM, physicians will receive a five percent bonus on top of their earned Medicare reimbursement. After 2025, APM physicians will receive a 0.75% annual payment increase.

By contrast, MIPS physicians receive no initial bonus and their Medicare reimbursement will adjust up or down based on performance. Payment adjustments begin at four percent and climb to nine percent over time. MIPS physiciains also will receive smaller post-2024 payment increases of just 0.25%.

Here’s the kicker. Once physicians elect to participate in APMs, the economic incentives will make it almost impossible to return to MIPS. It’s a governmental version of the Hotel California, “you can check in anytime you want but you can never leave.” ”[2]

By 2038, Medicare believes all physicians will participate in the APM track. Economics force the shift. Over time, the diverging payment incentives (performance-based payment under MIPS versus guaranteed bonuses under APM; much higher post-2024 payment increases (0.75% vs. 0.25%) under APM than MIPS) will create too vast a compensation gap for physicians to remain in MIPS.

“Leave the Gun. Take the Canolies.”

Gangsters drop like flies in “The Godfather” as mob war erupts. In one scene, disloyal Paulie Gatto drives a car with Clemenza in the front seat and Rocco Lampone in the back. Near the Statue of Liberty, they stop the car so Clemenza can heed nature’s call. After Clemenza leaves, Rocco puts two bullets in Paulie’s head.

Returning to the car, Clemenza instructs Rocco, “Leave the gun. Take the canolies.” – one of the great lines in American cinema.

CMS is deadly serious about making physicians more accountable for their treatment decisions and performance. They’re applying powerful incentives to encourage physicians to accept financial risk and improve treatment quality and efficiency.

Like the Godfather, CMS is patient, cunning and determined to win. Better, more effective healthcare for all Americans is at stake. Medicare is firing all its guns. It wants the canolies.

Like the Godfather, CMS is patient, cunning and determined to win. Better, more effective healthcare for all Americans is at stake. Medicare is firing all its guns. It wants the canolies.

When the dust settles, Medicare fee-for-service payment along with the SGR (and Luca Brasi) will “sleep with the fishes.”

Nathan Bays

Nathan Bays is the General Counsel to the The Health Management Academy (The Academy), Nathan serves as an advisor to the senior management team and health system leaders. As executive director of The Academy Advisors (The Advisors), Nathan works closely with the C-suite executives of member health systems on strategy, policy analysis and advocacy