December 8, 2015

Fujifilm’s “Moment”: Disruption, Adaptation and Health System Transformation

Almost every healthcare “transformation” discussion includes Kodak’s cautionary tale – how the once iconic company fails to embrace digital imaging, capsizes and drowns. The story’s moral is to embrace disruption, reinvent care delivery and thrive in the post-reform marketplace. Easier said than done.

These transformation discussions never discuss how Kodak’s chief rival, Fujifilm, navigated the same disruptive market environment, adapted and emerged more successful than ever. Health systems wishing to avoid Kodak’s fate will learn as much from studying Fujifilm’s successes as Kodak’s failures.

Market Evolution

In The Origin of Wealth, Eric Beinhocker applies evolutionary theory to explain market function, organizational competitiveness and wealth creation. In Beinhocker’s view, economies are complex adaptive systems that incorporate physical technologies (inventions), social technologies (organizational structures) and business designs to create more productive and wealthier societies.

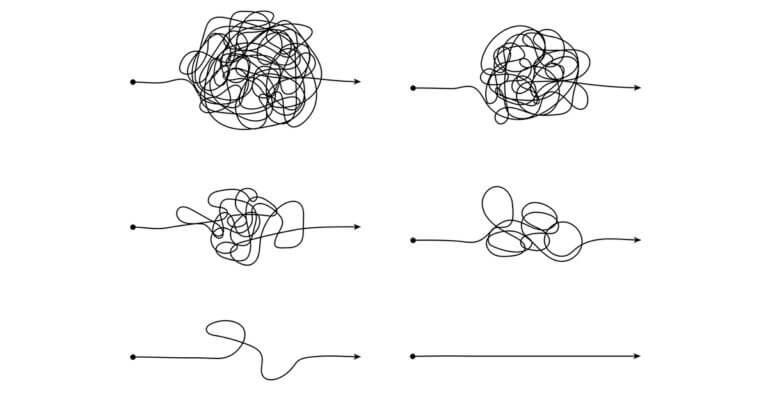

The core evolutionary formula (differentiation, selection and amplification) describes the three-stage process through which new products emerge, demonstrate their superiority and win market share. Relentless market repositioning creates winners and losers as customers purchase preferred products and services. The “fittest” companies survive by adapting to shifting consumer preferences.

It’s a widespread misconception that evolution results in “survival of the fittest.” Evolution actually causes “elimination of the weakest.” In business, companies that collaborate, pursue competitive advantage and keep customers’ interests first are most likely to “survive.” Strong companies that fail to adapt lose competiveness and market relevance.

Differentiation, selection and amplification unfold as industries transition. Disruption is the marketplace application of these forces on industry incumbents. IBM survived the transition from mainframe to desktop computing by reinventing itself as a services company. Digital Equipment Corporation’s (DEC’s) inability to manage the transition from mini to desktop computers led to its bankruptcy.

Film’s Millennial Challenge[1]

Approaching the new millennium, Kodak and Fujifilm expected a slow, manageable decline in film sales. They adjusted by selling digital cameras and aligned services (e.g. photo kiosks). The unanticipated popularity of cell phone cameras decimated demand for digital cameras. This created an “adapt or die” moment for both companies. How each responded is illuminating.

Fuji was always the “other “film company. Based in Japan, it never matched Kodak’s cache and brand strength. Despite equivalent quality, Fujifilm sold at a significant discount to Kodak. As an aspiring photographer with limited budget, Fuji was young Gaurov’s film of choice.

Kodak dominated the film market and generated huge profits. As turbulence hit, the company over-relied on brand strength and marketing to maintain competitiveness. Inconsistent leadership and a closed culture led to poor strategic decisions (imaging over chemicals), insufficient internal expertise in new business lines, bad market bets, ill-considered acquisitions and ineffective partnerships.

In contrast, Fuji embraced the digital transition and became the market leader in digital cameras. Strong leadership and effective movement into other business lines turbocharged its performance. When Shigetaka Komori became Fuji’s CEO in 2000, film generated sixty percent of the company’s profits, yet he chided the film divisions leadership for being “lazy and irresponsible” for failing to prepare adequately for the digital revolution. Here’s how Komori repositioned Fuji:

- Spent $9 billion acquiring forty companies, including $1.6 billion for a majority stake in FujiXerox. This provided incremental cash-flow as film sales dwindled.

- Cut billions of costs in two restructurings

- Employed its celluloid film expertise to launch cosmetics and LCD (liquid crystal display) business lines

- Moved aggressively into healthcare with investments in medical equipment, drugs and imaging

Today Fujifilm is a diversified company and more profitable than ever. Film accounts for less than one percent of revenues. In early 2012 as Kodak confronted bankruptcy, Komori described Fujifilm’s response to the disruptive threat posed by digital imaging,

“As time passes, the fact shows that when a company loses its core business, some companies are able to adapt and overcome the situation, while others are not. Fujifilm was able to overcome by diversifying.”

Leadership, culture and execution (not money, brand or market position) were the key attributes that enabled Fujifilm to succeed where Kodak could not.

Health Systems’ “Kodak Moment”- The transformation

Like Kodak and Fujifilm in the late 1990s, health systems know that attractive fee-for-service payment will not continue indefinitely. Value-based payment and competitors are emerging to displace health companies overly-dependent on traditional operating models. Despite this looming and disruptive threat, most health systems are not preparing to compete in market environments where the criteria for success are price, outcomes, convenience and customer experience.

Let’s make the Kodak-Fuji metaphor plain. Fee-for-service payment is film. Value-based payment is digital imaging. Health systems should answer the following questions honestly to assess whether they’re adapting to new market realities:

- Is the health system’s outpatient strategy focused on insanely convenient, low-cost and connected customer service or on converting to provider-based reimbursement, raising prices and closing offices at 5PM?

- Is the health system replicating high-end services in saturated markets or consolidating services into centers of excellence that have scale, better outcomes and lower costs?

- Does the health system have a digital strategy? Has it embraced tele-medicine and virtual clinics? Is the company increasing customer convenience or adhering to centralized, inconvenient delivery models?

- As consumers experience higher out-of-pocket payments, does the health system view price transparency as a competitive advantage or a threat?

- Do the health system’s service offerings create or diminish value for the communities they serve? Are disease management, wellness and post-acute care areas of key focus? Is the health system willing to cannibalize its acute operations to develop better community-wide health outcomes?

- Is the health system willing to partner with innovative companies that provide competitive advantage or does the health system believe these companies threaten its core businesses?

- Are the health system’s decisions driven by a short-term profitability or longer-term investments that improve customers’ health and well-being?

- Does the health system’s leadership and culture more resemble Kodak’s or Fuji’s? Can it make effective resource allocation decisions?

Darwinian Logic

Like film manufacturing in the late 1990s, healthcare delivery is at a significant inflection point. A constellation of politics, economic pressures and technological advances imperils current health company operating models. Value-based healthcare is good for consumers and good for the country. As evolution teaches, the “fittest” health companies will embrace this reality, adapt operations and thrive in the new marketplace.

Let’s give Charles Darwin the last word. He observed,

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.”

What is true in nature is also true in markets. Winning health companies adapt their business models to meet customer demands by delivering better care at lower prices in customer-friendly venues. They earn continued existence by following evolution’s three-stage adaptive process:

- differentiating their services in ways that customers value;

- customers selecting those services by purchasing them; and

- amplifying their presence by increasing market share.

By nature, complex adaptive systems advance civilization. Is American healthcare ready?

[1] Sources: Fujifilm Thrived by Changing Focus, Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2012;

The Last Kodak Moment and Sharper Focus: How Fujifilm Survived, Economist, January 2012

Fujifilm Develops a New Focus, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, August 2015

Gaurov Dayal is a physician leader with a passion for value based health care. He currently serves as SVP for Health Care System Solutions and Strategy for Lumeris, a leading population health management company.

Gaurov Dayal is a physician leader with a passion for value based health care. He currently serves as SVP for Health Care System Solutions and Strategy for Lumeris, a leading population health management company.

Previously he served as the first system Chief Medical Officer for both Adventist Healthcare and SSM Health and led the division of Health Care Finance and Delivery for SSM/Dean. In this role he had operational oversight for Dean Health Plan, Navitus (a PBM) and all value based care initiatives including two ACOs and CINs. His experience also includes founding a hospitalist company and working for McKinsey and Co as a health care consultant.