November 9, 2015

Getting Right with Consumers: Right Businesses. Right Places. Right Prices.

Market Corner Commentary for November 11, 2015-Getting Right with Consumers: Right Businesses. Right Places. Right Prices.

Consumerism has the force and precision of heat-seeking missiles. Customers flocked to Walmart because it offered more selection, greater convenience and lower prices than local “mom and pop” retailers. Amazon threatens Walmart because it offers even more selection, even greater convenience and even lower prices.

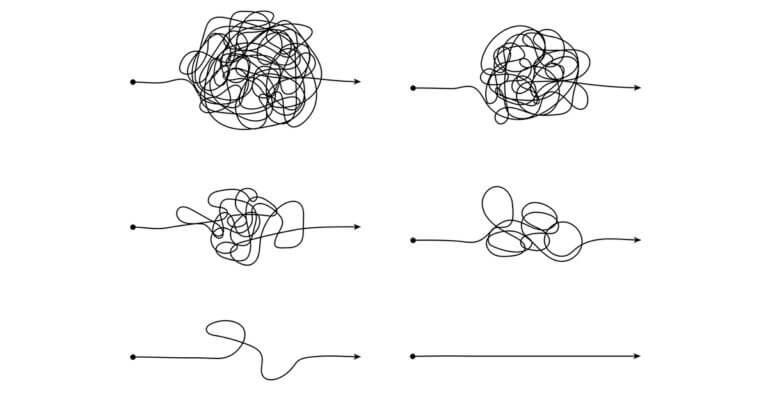

Consumerism is an intricate, never-ending dance between companies and their customers. Businesses exist only to find and keep customers. Success requires constant engagement, constant adjustment and a consistent ability to give customers what they want, where they want it at competitive prices.

Health systems are at the crossroads. Historically, they’ve executed transactions without involving customers. Patients followed “doctors’ orders”. While still early, patients/customers are taking more responsibility for medical decision-making. As healthcare becomes more retail, health companies must develop deep consumer instincts to reshape organizational missions, connect with customers and enhance strategic effectiveness.

Changing supply-demand relationships are forcing health companies to reconfigure business models, improve outcomes, lower costs and provide better customer service (consumerism). This “disruption” creates opportunities, but also increases failure risk for sub-optimal repositioning and execution. More than ever, health company leaders must understand their companies’ strengths, their customers’ needs and market dynamics when making strategic “bets” for post-reform success via consumerism.

Steve Jobs Returns

“Deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do. That’s true for companies and it’s true for products.” Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs continues to fascinate. With another “biopic” on Jobs now in theaters, his iconic stature grows even larger. Jobs strategic genius was knowing what customers wanted and giving it to them even before they knew they wanted it.

Jobs was focused, disciplined, often ruthless and had impossibly high performance standards. He needed all those traits to resuscitate Apple.

Eleven years after his ouster, Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997. The company was a shadow of its former self. Its market share had fallen from 16% to 4%. Its stock price had fallen from $70 to $13. As Jobs took the helm, Apple posted a $1 billion loss and was ninety days from insolvency.

Clearly it was time to “Think different.”

Jobs undertook an intense three-week business and product line review. Apple had become a bloated company with multiple business lines, numerous licensing agreements and dozens of inferior products tailored to the “whims of retailers”. Product teams couldn’t answer the simple question “which Apple products should I tell my friends to buy?”

Jobs exited the printer and server businesses, stopped providing software upgrades to Macintosh clones, eliminated 70% of the products and was still exasperated. Finally he drew a quadrant with “professional” and “consumer” columns (consumerism) and “desktop” and “portable” rows. Jobs decided to bet the company’s future on the Power Mac and PowerBook for the professional market and the iMac and iBook for the consumer market.

Through massive layoffs and corporate restructuring, Jobs narrowed and sharpened Apple’s business focus. He rekindled the magic and reconnected with consumers through imaginative products and the inspiring “Here’s to the Crazy Ones” marketing campaign. Under his leadership, Apple reconnected with its customers (consumerism), was immediately profitable and ultimately became the world’s most valuable and admired company.

Before Apple could recover, Jobs had to define the company’s problem and its causes. As legendary journalist Walter Lippmann observed, “For the most part, we do not first see and then define. We define first and then see.” Once Jobs identified the sources of Apple’s deep financial trouble, he was able to restructure, refocus and reinvent Apple.

Begin with Problem Definition

Health systems confront a similar, if less dire, challenge. Most acknowledge unsustainable business models yet struggle to realize meaningful change. Transformation begins with problem definition.

Cleveland Clinic CEO Toby Cosgrove distills the Clinic’s strategic vision as follows, “We’re in the sickness business. We need to be in the health business.” Banner Health’s CEO, Peter Fine, defined Banner as a clinical outcomes company in 2009: “focused on reducing care variability and increasing care reliability to deliver consistently superior outcomes.” Strong messages from gifted leaders, who understand the need to define problems before tackling them. Strategic clarity creates paths to success. Asking the right questions is essential.

Why Should People Buy Our Car? (Consumerism)

James C. Tyree grew up a Chicago south-sider. He earned undergraduate and MBA degrees from Illinois State University. After graduation in 1980, he joined Chicago-based Mesirow Financial as a research assistant and never left. Ten years later he was president; then chairman and CEO in 1994. Under his leadership, Mesirow catapulted from a financial boutique a major investment house. How did Tyree push his company toward greatness? By constantly asking himself and Mesirow employees, “Why should people buy our car?”

Under Tyree, Mesirow had an incessant focus on providing customer value. If Mesirow couldn’t give customers reasons to buy “their car,” they shouldn’t buy it. What’s most important in business is “seeing the pictures in the customers’ heads.” Tyree believed companies succeed by knowing their customers and striving to meet their needs. This requires a solid understanding a company’s competitive advantages, the ability to communicate winning value propositions to customers and the drive to constantly improve performance.

What Businesses Are We In?

Asking “what businesses are we in?” and “what businesses should we be in?” mirror the question “what problems are we trying to solve?” Here’s a partial list of potential business lines for health companies:

- Hospital operations

- Population health

- Health insurance

- Intellectual property development/licensing

- Elite referral medicine

- High-volume surgery

- Post-acute care

- Wellness

- Medical tourism

- International delivery

- Venture investment

While not mutually exclusive, these business lines have different operating profiles, customers and competitors. They require different strategies for growth, capital formation and risk management. It’s essential to understand sources of competitive advantage when determining organizational vision and strategy. Lacking clear understanding of competitive strengths and weaknesses leads to muddled decision-making and sub-optimal resource allocation.

No company can operate all these businesses. It’s time for health companies to pick their winners and attack the marketplace. American healthcare has deep problems that encompass lifestyle, treatment, engagement and effectiveness. Companies that define problems, narrow focus and deliver solutions will succeed where others stumble.

Embracing Disruption

Health companies are pursuing a wide range of post-reform business models. They are exploring new businesses, new partnerships, new forms of capital formation and new types of risk-taking. Transformation is hard, but has breakthrough potential.

The disruption roiling the health industry is particularly challenging for non-profit health systems. Inbred instincts battle against market-changing strategies. Powerful constituencies fight to maintain outdated privileges. In extreme cases organizational paralysis overwhelms mandates for change.

Given their legal basis, governance and community orientation, non-profit health systems are inherently conservative, strategically defensive and slow to change. This increases the stakes and leadership challenge for health company executives.

Organizational transformation cannot happen overnight. Health company executives must be both patient and lead with a sense of urgency. Creating selfless, team-oriented cultures that embrace change, appreciate customers and deliver value can be the difference between success and failure.

Going Through the Wall

Near the end of the movie Moneyball, Boston Red Sox owner John Henry offers to make Billy Beane baseball’s highest paid general manager. With his low-budget Oakland A’s, Beane had challenged baseball orthodoxy by using statistical science to optimize his team’s performance. In a remarkable scene, Henry explains disruption’s unrelenting logic:

You won the same number of games as the Yankees, but they spent $1.4 million per win and you spent just $260,000. I know you’ve taken it in the teeth, but the first guy through the wall always gets bloody, always. You’re not just threatening to the way they [baseball executives] do business. In their minds, you’re threatening the game. What you’re really threatening is their livelihood and their jobs. You’re threatening the very way they do things.

Every time that happens, whether it’s in government or business or whatever, the people holding the reins, those with their hands on the switch, go crazy. Anybody not tearing their team down and rebuilding it using your model is a dinosaur.

Enlightened health companies are reconfiguring business models. Their leaders are defining and attacking problems that plague American healthcare. They understand the need to overturn legacy systems and find creative ways to deliver better, more affordable and more convenient healthcare services.

Fighting for change against entrenched practices is bloody work. For revolutionary leaders, innovation has its own glory. Consider Steve Jobs, Jim Tyree and Billy Beane. Are they really “the crazy ones?” In the long run, markets recognize and reward value creation. U.S. healthcare is in the early innings of customer-focused transformation. The quality and sustainability of U.S. healthcare depend upon innovative companies that think and act “different.”

A version of this commentary first appeared in “Huron Perspectives”