August 23, 2022

Healthcare’s Jobs to Be Done (Part 1): A Primer

Editor’s Note: This is a series on jobs needed in the shifting landscape of healthcare. Part 2 of this series applies the Jobs framework to the needs of consumers and employers. The results are illuminating and somewhat surprising.

Part 1: A Primer

Part 2: Application

I’ve been an admirer of Clay Christensen’s work since the late 1990s. Shortly after he published The Innovator’s Dilemma in 1997, Christensen headlined a Merrill Lynch global retreat for managing directors. During his keynote address, he presented and applied his theory of disruptive innovation. I was mesmerized.

Christensen’s work was anything but theoretical. To its credit, Merrill had hired him to help reinvent the company’s golden goose. Merrill’s full-service brokerage business famously brought “Wall Street to Main Street.” It was core to the company’s identity, generated enormous revenues and profits, but was losing traction in the marketplace to online trading companies.

Following Christensen’s advice, Merrill proactively reorganized the company’s brokerage services to incorporate lower-priced personal trading and limited-service trading offerings. Mother Merrill still offered comprehensive brokerage services with full commissions to its customers that wanted the handholding. At the same time, the company expanded its market to attract more self-reliant and fee-sensitive customers.

The Merrill engagement illustrates the importance of rigorously understanding the pictures in customers’ heads when they “hire” companies to provide them products and services. These pictures represent customers’ “Jobs to be Done” (Jobs). I integrated this Jobs concept into my last book, The Customer Revolution in Healthcare: Delivering Kinder, Smarter Affordable Care to All Americans. It explains how “revolutionary” upstarts and incumbents will transform healthcare’s status quo business models.

The Customer Revolution published in September 2019, just four months before Clay’s untimely death from leukemia on January 23, 2020 at age 67. Among my proudest accomplishments as a writer was receiving Clay’s endorsement. Concise and to the point, it reads,

Johnson offers powerful direction to anyone looking to disrupt the healthcare system.

—Clayton Christensen, Kim B. Clark Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and bestselling author of The Innovator’s Dilemma

Earning Clay’s endorsement was not easy and took several months. Andy Waldeck, Clay’s partner at Innosight, was instrumental in making the request. Most writers mischaracterize Christensen’s work. Before agreeing to endorse my book, Clay asked his chief of staff to read the manuscript and certify its accuracy. Once that happened, Clay’s name and endorsement went on my book’s back cover.

As the healthcare ecosystem emerges from the COVID pandemic, payers and providers confront dynamic threats from new competitors that challenge traditional business practices. Despite these high stakes, most incumbents are complacent. They’re disconnected from their customers’ needs and making major strategic missteps.

Given the high stakes, it is wise for incumbents to revisit Christensen’s work on customers’ “Jobs to be Done” (Jobs). The Jobs framework offers insightful context and guidance for navigating through healthcare’s treacherous operating and market environments. It builds on the pathbreaking research of legendary Harvard Business School professor Theodore Levitt.

What Business Are You In?

Levitt famously observed that “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” He believed many companies forget they exist to solve customer problems and lose market relevance because of it.

Levitt’s 1960 article titled Marketing Myopia in Harvard Business Review was his most popular and influential. It became a manifesto for orienting companies to understand and satisfy customer needs. He believed too many companies defined themselves by their products and services. In doing so, they lost sight of the actual businesses they were running. Here’s Levitt on railroads.

The railroads did not stop growing because the need for passenger and freight transportation declined. That grew. The railroads are in trouble today not because that need was filled by others (cars, trucks, airplanes, and even telephones) but because it was not filled by the railroads themselves.

They let others take customers away from them because they assumed themselves to be in the railroad business rather than in the transportation business. The reason they defined their industry incorrectly was that they were railroad oriented instead of transportation oriented; they were product oriented instead of customer oriented….

Levitt’s keen insight was that customers actually “hire” railroads not because they’re railroads but because they transport people and products. Failing to understand why customers “hired” and “fired” them caused railroads to make strategic mistakes and misallocate resources. Levitt constantly pressed company leaders to determine what business they were in by defining and meeting customer needs.

Jobs to be Done

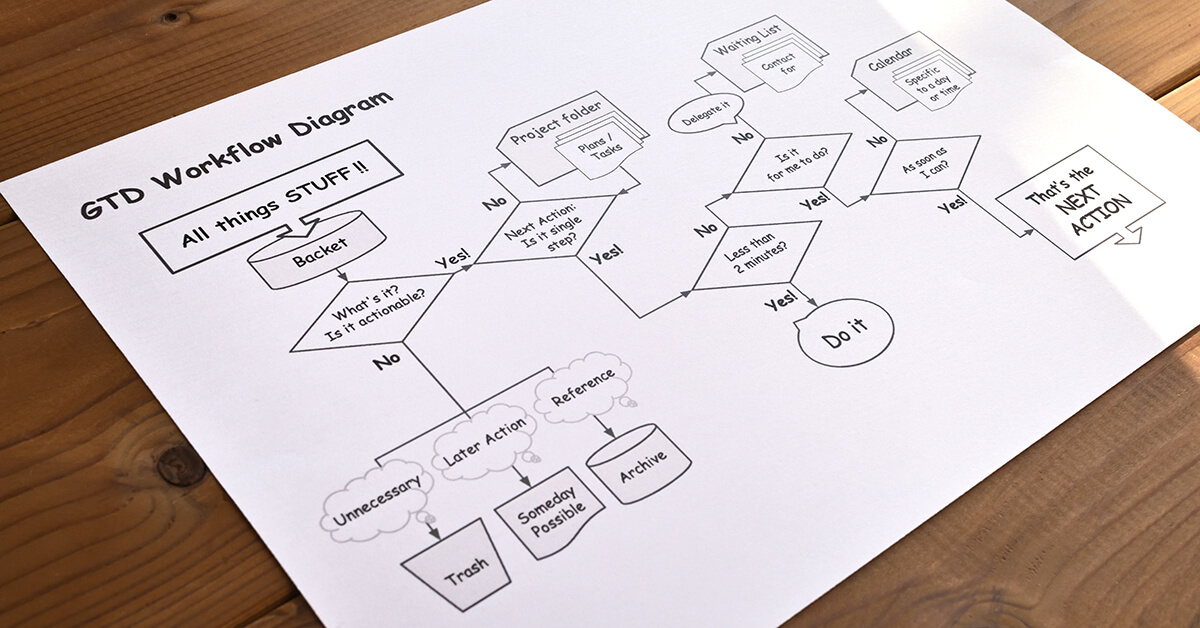

In a 2005 article titled Marketing Malpractice, Christensen and his fellow authors Scott Cook and Taddy Hall expand on Levitt’s customer-centric reasoning and introduce the Jobs-to-be-Done terminology. For them, the Job is the “fundamental unit of analysis” for companies to develop  and sell products to customers. As such, Jobs should drive market segmentation and innovation.

and sell products to customers. As such, Jobs should drive market segmentation and innovation.

The structure of a market, seen from the customers’ point of view, is very simple: They just need to get things done, as Ted Levitt said. When people find themselves needing to get a job done, they essentially hire products to do that job for them.

The marketer’s task is therefore to understand what jobs periodically arise in customers’ lives for which they might hire products the company could make. If a marketer can understand the job, design a product and associated experiences in purchase and use to do that job, and deliver it in a way that reinforces its intended use, then when customers find themselves needing to get that job done, they will hire that product.

In a 2016 HBR article titled Know Your Customers “Jobs to be Done,” Christensen, Taddy Hall, Karen Dillon and David Duncan explain how a deep understanding of customers’ needs can guide innovation and enhance market competitiveness. From their perspective, a strategic focus on Jobs has these characteristics and attributes:

- Jobs are more than just tasks. They represent what individuals hope to accomplish in specific circumstances. As such, they are conceptually holistic and experienced based.

- The customer’s circumstances are more important than customer characteristics, product attributes, new technologies or trends.

- Good innovations solve problems that formerly had inadequate solutions or no solutions at all.

- Jobs are never simply about function. They have powerful social and emotional dimensions.

Christensen’s classic “milkshake” case study from Marketing Malpractice illustrates the analytic power of the Jobs framework. It demonstrates how companies should center innovation on solving customer problems.

Here’s the setup. A fast-food restaurant used consumer data and focus groups to test market thicker, more chocolaty, cheaper and/or chunkier milkshakes. Despite clear consumer feedback, none of these marketing strategies increased sales. Enter Jobs theory and its application.

Using the Jobs framework, Clay’s team conducted a deep sales inquiry to understand why customers were “hiring” milkshakes. The results were surprising. Customers bought forty percent of all milkshakes before 8:30 AM. They were generally alone and bought only milkshakes that they consumed in their cars. From focus group discussions, the team learned that these customers hired milkshakes because they were filling, long-lasting, weren’t messy, were consumable with one hand and relieved the tedium of long commutes.

Customers buying milkshakes after 10 am were very different They were typically parents hiring milkshakes to placate their children. The trouble was that milkshakes weren’t doing this Job well. Children struggled to consume the milkshakes long after their increasingly frustrated parents had finished their meals.

With this granular market knowledge, it was clear that customers were hiring the milkshakes for two different Jobs. A one-size-fits-all solution didn’t work well for either. That’s why the various innovations to expand sales had failed.

For commuters, making the milkshakes longer-lasting (thicker), more interesting (with small fruit chunks) easier/faster to pick-up and cheaper to buy turbocharged sales. For parents, the solution became downplaying milkshakes and offering other snacks that made their kids smile without wasting precious time.

Understanding the two Jobs led the company to implement different product innovations for each buyer type. The results were spectacular and paid dividends through increased sales, market expansion and greater customer loyalty. Companies that approach Jobs in this way create “purpose” brands that tightly align with customer needs. As the authors note,

By understanding the job and improving the product’s social, functional, and emotional dimensions so that it did the job better, the company’s milk shakes would gain share against the real competition — not just competing chains’ milk shakes but bananas, boredom, and bagels.

This would grow the category, which brings us to an important point: Job-defined markets are generally much larger than product category–defined markets. Marketers who are stuck in the mental trap that equates market size with product categories don’t understand whom they are competing against from the customer’s point of view.

Notice that knowing how to improve the product did not come from understanding the “typical” customer. It came from understanding the job.

Finding Jobs to be Done

In Know Your Customers’ “Jobs to be Done,” Christensen and his fellow authors suggest that companies should ask themselves the following five questions about the Jobs that their customers are trying to solve.

- Do you have a Job that needs to be done? Often the greatest innovations come from intuition and observation. Examine operations for poorly-solved problems that matter to customers.

- Where do you see non-consumption? This is often the richest source for missed opportunities. Learn from those who aren’t hiring your product or service. Understanding and solving their problems opens new markets.

- What workarounds have people invented? Be alert to circumstances where customers apply inefficient solutions to pressing problems. They gum up the works, create frustration and may cause customers to “fire” you.

- What tasks do people want to avoid? Poor and untimely service creates “negative jobs” for customers. They avoid them whenever possible. Finding solutions that eliminate negative jobs delight customers and build brand loyalty.

- What surprising uses have customers invented for existing products? Be alert to new uses for established products. In these cases, customers find Jobs for you.

I believe the Jobs-to-be-Done framework crystalizes the strategic challenges that healthcare companies now confront as they reposition to embrace value, consumerism and product differentiation. Identifying and solving Jobs brings companies into closer alignment with their customers’ needs. Doing Jobs well creates brand equity and increases consumer loyalty.

In so many ways, healthcare incumbents have lost touch with their guiding purpose. They’re floundering in seas of dissatisfied customers beset with problems that make engagement worse rather than better. Clinging to existing business models that create problems for customers is not a sustainable long-term strategy.