May 28, 2024

Heart Failure Mortality Rises as Primary Care Access Declines

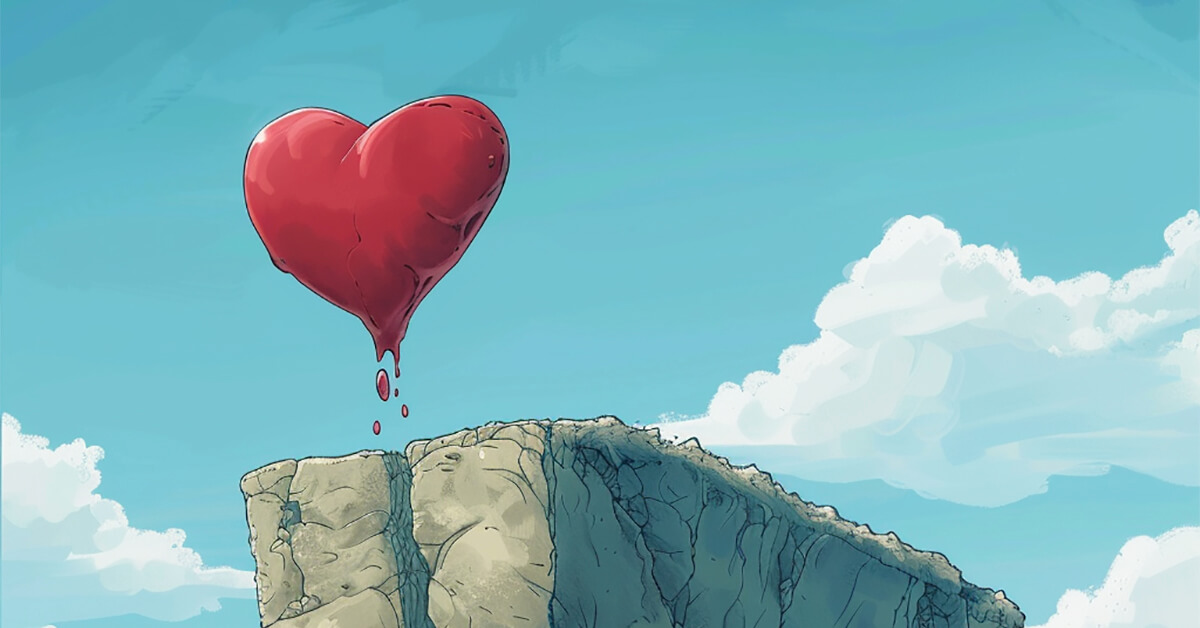

A few times during my journalism career I’ve seen seemingly unrelated trends bump into each other and spark a novel insight. This happened recently when I was working on a piece for WebMD about the surge in the heart failure mortality rate over the past decade. I wondered why this kind of death should be growing in a rich country like the U.S., especially after dropping during the 2000s.

The experts I interviewed mostly blamed the significant increase in obesity and diabetes during recent years. A prominent government scientist, Veronique Roger, MD, opined that the blame shouldn’t be on doctors. People were eating the wrong foods, ignoring fresh items in favor of food products created by an industry more interested in profits than in health.

I couldn’t argue with that. Still, I asked Marat Fudim, MD, a co-author of the study on the increasing heart failure mortality rate, whether the primary care crisis — a chronic shortage of primary care physicians that is continuing to worsen — might have something to do with it.

Fudim replied that the reversal in the heart failure mortality trend might be related to problems in the healthcare system. Partly because of the shortages in primary care, he said, access to care is limited in many areas, prevention and chronic care are being underemphasized, and some heart failure patients are not getting the care they need.

Roger agreed, pointing out that the substantially higher heart failure death rate among Black people, compared to Whites, is probably connected to their difficulties in accessing healthcare.

The Boom in Concierge Medicine

While researching that story, I happened to read an article in Kaiser Health News about another important trend: Primary care practices owned by health systems are starting to adopt the concierge care model. While concierge medicine has been around for more than 20 years, most of its practitioners, until recently, had been independent. The idea that health systems were now embracing this concept seemed alarming.

The concierge model, as the Kaiser Health News piece observes, evolved in wealthy enclaves in Florida and California. Upper-income people were more than willing to spend an extra few thousand dollars every year to ensure better access to primary care physicians.

Later, with some help from concierge companies that offered turnkey services, more and more practices across the country began to provide concierge care. Primary care doctors oppressed by micromanaging health plans were glad to earn more money while seeing fewer patients. Some of them continued to accept insurance; others cut the cord entirely.

Here’s the headline: Physicians who fully accept the concierge model have only a few hundred patients compared to 2,000 in a typical primary care practice. Consequently, the growth of concierge medicine means less access to primary care, particularly for lower-income people.

According to the Kaiser Health News article, the concierge primary care services offered by health systems can cost anywhere from $2,500 to $4,000 a year or more. That’s in addition to the increasingly high copayments and deductibles that patients already have to pay — not to mention the facility fees tacked onto the charges of hospital-owned practices.

Nationally, large nonprofit health systems are following this path, for example: Northwestern Medicine in Chicago, Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, University Hospitals in the Cleveland area, Baptist Health in Miami, and Inova Health in Virginia.

Concierge care offers multiple benefits to these health systems, Kaiser Health News notes. Not only do they reap extra revenue from the concierge fees, but the patients who agree to pay those fees tend to be well-off and well-insured. These are the ideal patients for a health system that employs primary care doctors to generate referrals to its hospitals and other facilities.

The results are sadly predictable. One study found that concierge medicine enrollment corresponded with a 30% to 50% increase in healthcare spending by patients while having no impact on mortality rates.

It seems inevitable that as concierge care grows, primary care access will decrease. And it’s already pretty bad. A recent report from the Physicians Foundation and Milbank Memorial Fund found that 29% of adults and 14% of children do not have a regular source of care. Many of those seeking care wait six to nine months for a new patient appointment; even established patients can wait days or weeks for a sick visit. Another report from the Commonwealth Fund said that a third of Medicare beneficiaries wait more than a month to see a physician. Of course, people can go to an emergency department or an urgent care clinic, but that’s not the same as having a physician who knows your history and treats your chronic conditions.

Which brings us back to heart failure. If it is true that the health system is partly responsible for the climbing heart failure death rate, then primary care is a big part of that problem. Until we fix primary care, more and more people will develop the comorbidities that lead to heart failure, and a growing number of those with the condition will not receive the care they need. It’s time to look squarely at why our healthcare system often fails to provide good access and high quality care, and what role our profit-driven, fee for service payment model plays in that.