July 14, 2022

How Long Are You Going To Live?

Life Expectancy Is Predictable

If you are you interested in your life expectancy based on your location, place your ZIP code into Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s internet site. You can easily compare ZIP code results if you are thinking of relocating. As individuals, we want to know for personal reasons, but the government and society in general should also pay attention to life overall expectancy to effectively plan. Building infrastructure, anticipating needs, producing products and a host of other socioeconomic exigencies all depend on demand, which increases as life spans extend.

Moreover, a new, first-of-its-kind map from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS, a Division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), encourages one to explore detailed life-expectancy estimates across the United States, down to the census-tract level. Within a ZIP smaller census tracts (of about 1,200 to 8,000 people; 4,000 average) yield more specific, geographically sized, life-expectancy averages.

Obviously, an average can include wide variation even among people living in the same census tract. Locations just a few blocks have gaps as much as a decade of average life expectancy.

America Continues to Fall Behind

Even more disquieting than life-expectancy gaps in America is the sad fact that life expectancy in the U.S., even before COVID, has been dropping faster than in other developed nations. For the past 40 years, our nation’s life expectancy has fallen further and further behind peer nations. Sadly, since 2014 this negative trend has accelerated, possibly due to the diseases of despair — drug addiction, alcoholism and suicide.

Obviously, COVID lowered life expectancy across the world. The decrease in life expectancy in the U.S. was 2.26 years from 2019 to 2021. Astoundingly, during the same time peer nations only lost 0.12 years, thus widening the gap between our nation and others to more than five years. We are in a globally connected and competitive world. If we can’t keep up with life expectancy, we can expect our standard of living to also fall behind. From 1900 to 2000 America led the world, now we are vying with China, India, Japan, and Brazil. Who will lead from 2000 to 2100 is a topic for discussion?

Bias Persists in Life Expectancy

Concerningly, American Black and Hispanic populations’ average losses exceeded other populations at home as well as total population in other high-income countries. Additionally, lower socioeconomic status translates statistically to increased mortality among working-age adults.

Further, subpopulations with a 4-year college degree experienced life expectancy lengthening versus shortening for those without this educational experience. Household earnings also parallel life expectancy. At the extremes, comparing the top and bottom 5% household earnings from 2001to 2014 at 40 years of age showed a life expectancy gap of almost ten years.

Social and economic forces are central drivers of the decline in U.S. life expectancy. No matter how much money America spends on healthcare, and it spends the most by far of any nation in absolute and per-capita measures, average life expectancy for the nation’s total population will not increase.

What Would You Pay for a Healthier Life?

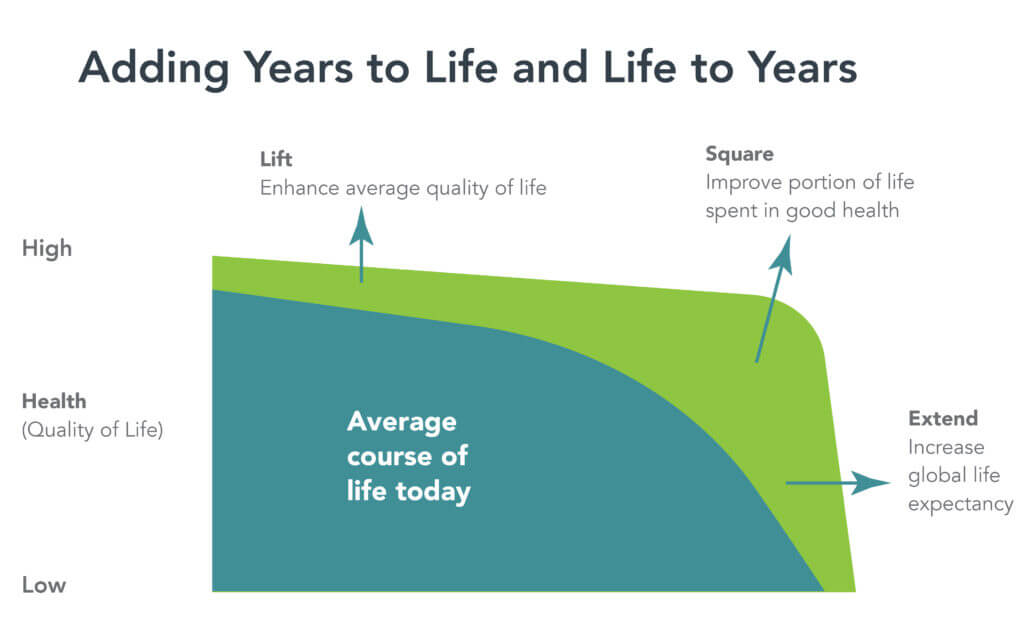

What is the value of making lives longer and healthier? Is living longer no matter what more valuable than staying healthy? How does the value of treating aging comprehensively compare to eradicating diseases specifically? These thoughtful questions were addressed using an economic model rather than the traditional biological model in a University of Oxford study, The Economic Value of Targeting Aging, and a McKinsey Health Institute paper entitled Adding Years to Life and Life to Years.

Life expectancy has increased dramatically over the past century but has decreased over the past few decades as noted above. Chronic noncommunicable diseases, and the number of people suffering from them, have also increased over the last century, but much more rapidly over the past few decades, now accounting for over 70% of deaths in America.

Fee-For-Service Exacerbates Disappointment

Using a census tract or ZIP code’s life expectancy as a cost-free longitudinal metric to reward healthcare systems, or others interested in mission-driven well-being and health, makes sense. The current fee-for-service system has proven that adding expense does not lead to longer life expectancy. In fact, America continues to fall behind other nations that have embraced universal healthcare.

“We spend a fortune on medical care and we’re a high-income country. We should be able to do far better,” implored Noreen Goldman, a demographer at Princeton University.

Now is the time for a change with an established metric and a novel approach.

Just adding years of unhealthy live is not a worthy goal, nor is addressing a specific disease. Measuring healthy aging by the “value of a statistical life” (VSL) places a monetary value on living a longer and healthier life. Total life expectancy as a metric has been a standard, but now VSL gives a more comprehensive and inclusive measurement. Focusing on a healthy and functional life creates a virtuous cycle for a more successful society by adding economic benefits that can be reinvested.

How Much Is Healthy Life Worth?

On average, people spend about 50% of their lives in less-than-good health, a percentage that hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years. Overall life expectancy has increased, which increased the absolute total time in poor health. Thus, the total number of years in poor health has increased because the duration of life in good health has remained broadly constant.

In addition to the obvious disappointment and pathos of adding years of unhealthy life, the economic consequences can be devastating for an individual, family and society. Medical care is expensive and sick people are not productive. Thus, society consumes more than it produces. Multiplied out, this imbalance hobbles or even bankrupts society.

Thinking of prevention as an investment rather than a cost could address 40% of the disease burden. The concept of “squaring the healthy life expectancy curve,” namely increasing the time spent in good health both in absolute and percentage time, is an admirable goal with not only altruistic benefits but also economic well-being. Increasing the number of years a person is healthy and productive by decreasing the time spent sick and needy helps the individual and society in general.

Source: Adding years to life and life to years. McKinsey & Company. June 28, 2022.

The above is an effective educational graphic gleaned from the McKinsey Health Institute.

Live Longer and Better

The obvious goal for individuals, communities, nations, and even the world should be to increase years of healthy life. Focusing on prevention before chronic illness takes root is an equally apparent activity. Overcoming existing economic barriers by encouraging healthy behaviors has been accomplished in 71 communities for over four million people who have embraced the Blue Zones Project.

Health and well-being are more than the absence of disease and impairment. Involving four major characteristics makes for a better life:

- Personal behaviors — activities, diet, sleep, and work

- Personal attributes — genetics, traits, finances, and medical benefits

- Interventions — clinical, resources, and incentives

- Environmental attributes — built environment, access to information, security, and climate.

Understanding the difference between a longer life and a healthy longer life is necessary to take actions to accomplish a noble goal — a longer, happier and healthier life.

Sources

- Life expectancy: Could where you live influence how long you live? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2022, July 5). Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/interactives/whereyouliveaffectshowlongyoulive.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, March 9). Life expectancy data viz. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/life-expectancy/

- Venkataramani, A. S., O’Brien, R., & Tsai, A. C. (2021, February 16). Declining life expectancy in the United States-the need for social policy as health policy. JAMA. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/articleabstract/2776338

- Masters, R. K., Aron, L. Y., & Woolf, S. H. (2022, January 1). Changes in life expectancy between 2019 and 2021: United States and 19 peer countries. medRxiv. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.04.05.22273393v1

- Scott, A. J., Ellison, M., & Sinclair, D. A. (2021, July 5). The economic value of targeting aging. Nature News. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s43587-021-00080-0

- Coe, E., Dewhurst, M., Hartenstein, L., Hextall, A., & Latkovic, T. (2022, June 28). Adding years to life and life to years. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.mckinsey.com/mhi/our-insights/adding-years-to-life-and-life-to-years

- Stein, R. (2022, April 7). S. Life Expectancy Falls for 2nd year in a row. NPR. Retrieved July 12, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/04/07/1091398423/u-s-life-expectancy-falls-for-2nd-year-in-a-row

Read other 4sight Health articles discussing U.S. life expectancy and disparities.

Separate And Unequal, Part 1 and Part 2, David W. Johnson

Scientific Aging: The Genetic Basis for Longer, Healthier Lifespans, David W. Johnson & Leroy Hood, MD, Ph.D.

The Science of Wellness, Leroy Hood, MD, Ph.D

Pandemics Cubed: Social Injustice and Chronic Disease Amplify COVID-19’s Virulence, Allen Weiss, MD

The Next Moonshot: Moving to Reverse America’s Declining Life Expectancy, Allen Weiss, MD