November 4, 2019

Mission-Critical Repurposing: Converting Aging Senior Living Properties to Affordable Housing

In 1908, the Jewish Home for the Aged of the Northwest opened in St. Paul, Minnesota, serving eight residents. As the facility deteriorated, the local Jewish community raised funds and opened a new Jewish Home in 1923 across the street from the world-famous Minnesota State Fair.

Notably, they built the new facility exclusively for “reasonably healthy residents.” This changed in 1947, when the Daughters of Abraham, a charitable group, raised enough money to care for the chronically ill within the Jewish Home facility.

In 1971, Jewish Home joined forces with another Jewish-affiliated organization to launch a new, and much larger Senior Living facility named Sholom Home. Through extensive fundraising, the sponsors modernized, expanded and upgraded Sholom Home multiple times to ensure adequate housing, medical care and occupational therapy services for residents.

As the new millennium approached, Sholom Home had fallen into disrepair and desperately required renovation. By then, however, the Jewish community had largely moved away from the neighborhood which further diminished Sholom Home’s marketability. Rather than renovate, the sponsors closed the facility in 2009 and moved to a new campus where over 1,000 residents now receive care.[1]

A decade later, the old Sholom Home building is unoccupied and decrepit. The current owners have failed to secure sufficient funding to gut and remodel the property as a modern assisted living facility. As the years pass, the price tag to modernize keeps rising.[2]

This plight is increasingly common in urban settings across the United States. A high percentage of SNFs and nonprofit senior facilities are now over 30 years of age. Subject to local economic reality, the vagaries of fundraising and evolving demographics, many suffer from reduced use, disrepair and abandonment and a lack of capital investment.

What should be done with these underperforming and redundant properties?

America faces a growing need for moderate-income affordable housing. Sponsors struggling with declining properties can convert underperforming Senior Living properties into badly needed affordable housing with affiliated healthcare services. In the process, these sponsors can find incremental resources to fund their organizational missions.

The Problematic Obsolescence of Nonprofit Senior Living Properties

For over a century, America’s nonprofit Senior Living institutions have cared for residents from various faiths, ethnicities, and fraternal memberships. To do so, they relied heavily on charitable giving.

Today, many long-standing facilities operate in neighborhoods whose demographic compositions no longer match those of their sponsoring communities. Changes in ethnicity, religious affiliations, income levels, age mix and lifestyle preferences influence, often in negative ways, the volume of seniors who choose to reside in these long-standing local facilities.

Healthcare referral patterns also have changed. Decades-old Senior Living and Skilled Nursing facilities suffer from declining occupancy and lower payment rates. Many also suffer from declining financial performance.

Consequently, many facilities and even multi-level care campuses have become antiquated with marginal or no profitability. This drains vital monies from the balance sheets of sponsoring organizations which are already struggling to attract sufficient charitable donations to sustain their missions. Board fatigue and local indifference often accompany the financial decline.

Struggling facilities are increasingly finding themselves pressured by new competitors offering upscale amenities. Many of these newer Senior Living campuses, whether proprietary or nonprofit, operate as regional rather than single-site providers. This “system” approach is typically more efficient, and supports provision of more complex, and cost-efficient support services and medical care. They often make substantial investments in campus amenities and marketing to continue and even increase their attractiveness to new residents.

For older, traditional facilities, maintaining profitability under such circumstances is a losing proposition. Facing this financial pressure, sponsors often sell marginal facilities at fire-sale prices. Distressingly, many sponsors sell or transfer properties to new operators for purposes unrelated to their original charitable missions. In too many instances, sales proceeds barely cover the cost of relocating current residents.

There is a better way. Ten thousand baby boomers a day are turning 65. A sizable percentage have insufficient financial resources to manage their post-retirement lives. Finding affordable housing is usually their biggest challenge.

Purposeful Renewal

Rather than accept the grim choices described above, facility owners can convert underperforming Senior Living properties into badly needed affordable senior housing. A powerful financing mechanism, Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), facilitates these conversions through Substantial Rehabilitation Renovation Partnerships.

The competitive value of LIHTC’s can vary from market to market depending on the following factors: the speed of renovation; the number of subsidized units developed; local demand for affordable housing; adjacency to services/stores; and overall project cost.

While the 2017 Tax Bill reduced the value of tax credits for some higher taxed buyers, conditions remain favorable for developing affordable housing. State and local government zoning provisions typically allow higher unit density allocations for affordable and senior housing projects. This facilitates more rapid planning approvals than can be secured for newly proposed urban infill construction. Rehabilitation projects also generally cost less than new facilities to develop. Together, these factors make Senior Living facility conversions an attractive alternative for developers competing for limited grants, subsidies and tax benefits.

Aging Senior Living facilities are often located near existing residential amenities such as public transportation, walkability, services etc. which improves their competitive position when applying for low income tax allocations. Many facilities also have land in the form of parking lots or single-story building components that can support higher-density construction.

Additionally, common areas in Senior Living facilities can accommodate outside service vendors, including primary care clinics, PACE programs or adult day health providers. Adding these types of services helps meet essential geriatric aging in-place needs while generating incremental revenues in the form of rent or supportive services subcontracts.

These older, marginally performing, market-oriented Senior Living facilities often already serve populations whose “middle incomes” qualify for the lower income rents LIHTC’s mandate, reducing resident displacement while providing those moderate-income residents the mental relief that future rent affordability offers those of modest means. Sponsors can apply funds raised through the sale of existing property structures for investment in new facilities and/or specific charitable purposes.

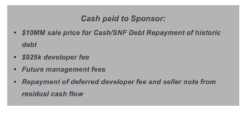

In addition, sponsors with strong development expertise or the ability to out-source such services to qualified third-parties are allowed to earn development fees through the low-income housing tax-credit conversion process. Sponsors can also continue to manage the converted (high-demand) affordable properties and earn the operational management fees that they can apply to meeting their charitable missions.

The historic reputations of Senior Living facilities often add luster to projects that convert those facilities to affordable housing. Granting agencies / foundations and prospective residents connect with the sponsor’s original legacy and mission. Acknowledging the facility’s past while adapting it to serve the needs of today and tomorrow enhances the credibility of institutional affordable housing grant funders.

Conversion Strategy Primer

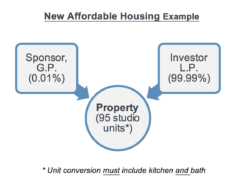

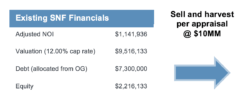

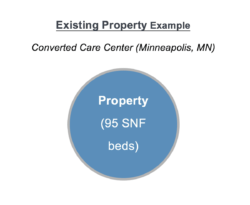

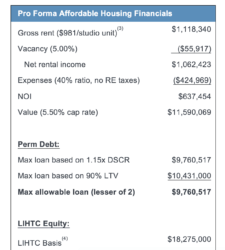

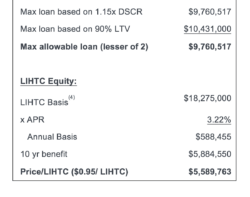

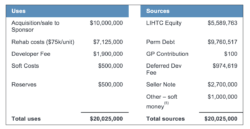

The following illustrative example details the process of converting aging Senior Living properties into affordable senior housing projects. The example is fictional but relies upon an actual SNF property with 95 beds and a current valuation approximating $10 million. Sponsors can apply sale proceeds from the “as-is” property for investment in a replacement community or placed in a foundation that assists seniors with the cost of aging.

The new affordable housing projects contains 95 studio and one-bedroom apartments with kitchens and baths. Tax credits and supplemental grants are coupled with residual government insured mortgages to reduce capital costs. Leveraging lower shelter rent payments from residents can make the affordable housing project financially sustainable. The community benefits by repurposing a money draining business and outdated building with needed affordable housing.

Converting Underperforming/Redundant Market Rate Properties to Affordable Senior Housing or Medicaid Waiver Assisted Living

![]()

Conclusion: A Growing Reality Meets a Looming Need

Ten years from now, more than half of middle-income Americans age 75 or older will struggle to afford their assisted living rent and medical expenses.[6] Too many middle-class elderly people do not qualify for government support yet cannot maintain modest lifestyles in retirement. Rising medical and housing costs exacerbate their plight. For a nation where the moderate-to-middle class comprises 50 to 65% of the overall senior population,[7] this future is untenable.

Compounding the problem, the current mix of aged Senior Living facilities often does not match evolving consumer demands. Handicapped by a lack of resident demand, these facilities suffer from deferred capital investment which only worsens their competitive position, and thus the funding necessary to meet the care needs for the frail elderly they serve. These facilities are both underutilized and quickly becoming redundant in today’s growing competitive market rate Senior Living marketplace.

At the other end of the economic spectrum, affluent seniors avoid aging properties like the plague. Seniors in the upper 10-20% income brackets demand amenity-rich facilities that older properties targeting this private market sector cannot offer.

Converting aging Senior Living facilities to affordable housing with aligned social services makes public policy and financial sense. Optimal “solutions” include the following attributes:

- Leveraging Social Service dollars and Medicare and Medicaid entitlement benefits in combination with tax credits to holistically respond to seniors’ overall housing and care needs;

- Providing support services within the cost-efficient, economies-of-scale and population health management delivery environment that a congregate living setting provides;

- Applying technology and support services that enable healthy seniors to live in their own apartment homes longer;

- Working with local governmental housing authorities to establish “frailty” as an admission priority for affordable housing in combination with the other economic, racial, ethnic and fair housing preferences mandated by both tax-credit and subsidized senior housing funders.

Conversions put money in the original sponsor’s pocket for redeployment in new facilities or for community-based programming. Co-locating PACE, FQHC clinics or ADHC programs within these rehabilitated affordable senior housing can also serve as a better approach to care delivery than Medicaid-funded skilled nursing. Combined, these services can meet the need for low to mid acuity assisted living level care.

Beginning in the early 1900s, Americans recognized the need to build humane and caring facilities for the nation’s elderly. In response, sponsors, operators and charitable givers created not-for-profit senior living facilities with a mission-driven spirit.

Conversion of these now aging Senior Living facilities to affordable housing maintains this honorable legacy by meeting a pressing current need. By repurposing their past investments, sponsors can maintain their ongoing charitable missions.

Bill and Dave discuss this topic in an episode of the Cain Brothers House Calls podcast. Find all episodes of House Calls here.

Sources

- http://www.mnopedia.org/group/sholom-home-st-paul-and-st-louis-park

- https://www.parkbugle.org/public-meeting-on-sholom-home-future-to-be-held-march-7/

- Equals 60% of AMI.

- 90% of Acquisition cost + Rehab Costs + Developer Fee + 50% of Soft Costs. Assumes not located in Qualified Census Tract (QCT). If property located in QCT, 130% boost to LIHTC basis, generating greater credit equity.

- Housing trust funds, HOME funds, etc.

- https://khn.org/news/in-10-years-half-of-middle-income-elders-wont-be-able-to-afford-housing-medical-care/

- https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/26/how-many-americans-qualify-as-middle-class.html

Co-Author

Bill Pomeranz is a senior banker in the Firm’s Post-Acute Care and Senior Living Advisory practice. Mr. Pomeranz joined Cain Brothers in 1998 and has over 35 years’ experience advising post-acute care providers, CCRCs, and senior living facilities. Since joining Cain Brothers, Mr. Pomeranz has obtained over $4 billion in both tax-exempt and government agency mortgage new start and expansion financings for his CCRC and long-term care clients. Mr. Pomeranz’s notable transactions include financings for the Buck Institute for Research on Aging; tax exempt CCRC bond issues for Moldaw Residences, Los Angeles Jewish Home for the Aging, Arizona State University, and the Pacific Retirement CCRCs in Portland, Ft. Worth, and Seattle. He is also very active in Senior Living and Post-Acute M&A with the sale of Meriter Retirement Community to Pacific Retirement Community; Longhorn Village to Presbyterian Brazos Homes, and the sale of Wyndemere Retirement Community to Life Care Services. He is also active in negotiating post-acute and hospital system joint-ventures designed to expedite acute discharge planning while creating platforms for population health management.

Bill Pomeranz is a senior banker in the Firm’s Post-Acute Care and Senior Living Advisory practice. Mr. Pomeranz joined Cain Brothers in 1998 and has over 35 years’ experience advising post-acute care providers, CCRCs, and senior living facilities. Since joining Cain Brothers, Mr. Pomeranz has obtained over $4 billion in both tax-exempt and government agency mortgage new start and expansion financings for his CCRC and long-term care clients. Mr. Pomeranz’s notable transactions include financings for the Buck Institute for Research on Aging; tax exempt CCRC bond issues for Moldaw Residences, Los Angeles Jewish Home for the Aging, Arizona State University, and the Pacific Retirement CCRCs in Portland, Ft. Worth, and Seattle. He is also very active in Senior Living and Post-Acute M&A with the sale of Meriter Retirement Community to Pacific Retirement Community; Longhorn Village to Presbyterian Brazos Homes, and the sale of Wyndemere Retirement Community to Life Care Services. He is also active in negotiating post-acute and hospital system joint-ventures designed to expedite acute discharge planning while creating platforms for population health management.