September 17, 2024

Mothers Are Suffering, and Healthcare Leaders Are Critical to the Solution

Maternal health in the U.S. is poor and declining. As a healthcare leader, this isn’t news to you. However, the power you have to improve it might be surprising.

You likely know maternal mortality is worse in the U.S. than any other wealthy nation, and outcomes are the worst for Black Americans. Unfortunately, poor maternal health outcomes perpetuate beyond the first year postpartum. For U.S. mothers, health over the course of their lives is worse than that of fathers or peers without children. The outcomes are so dire the Surgeon General put out an official advisory in August, “Parents Under Pressure.”

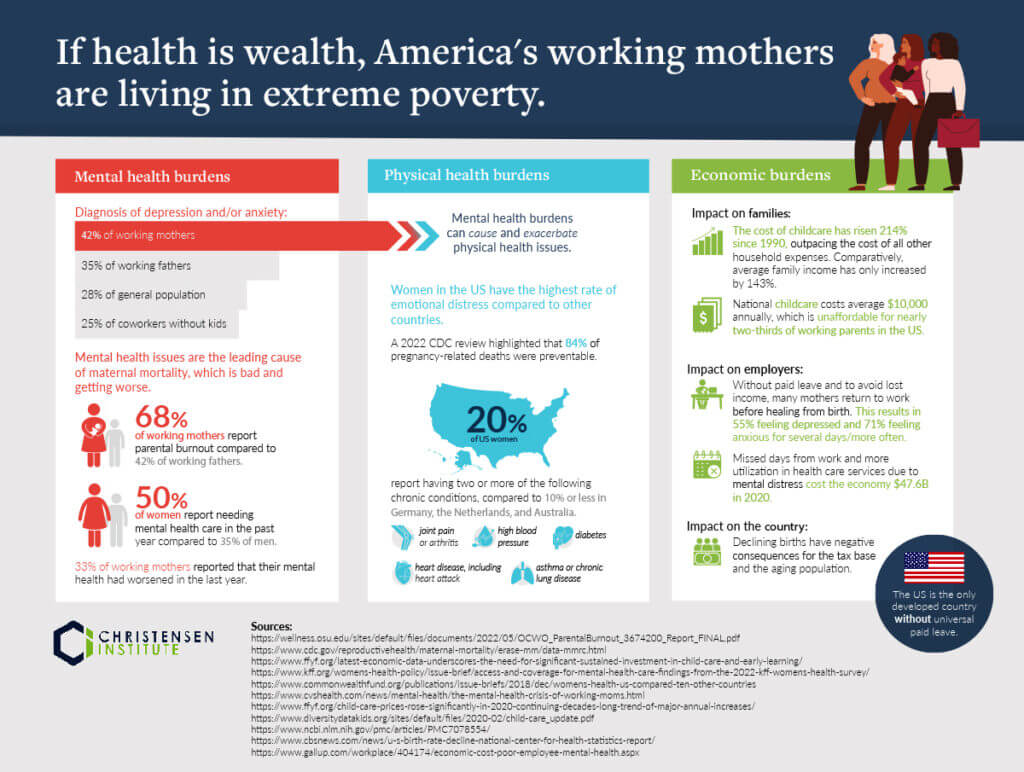

The infographic below highlights just how disparate maternal mental and physical health outcomes are and how these issues are compounded by economic burdens.

What’s Driving These Poor Outcomes?

Negative maternal health outcomes are rooted in a healthcare system and national ecosystem that perpetuate them. Poor maternal health outcomes are a systemic problem, not an individual problem. And systemic problems require systemic solutions.

At their roots, many of the misalignments between work and home life are the result of societal and employer structures that expect mothers to work like they aren’t parents, and to parent like they aren’t employees. That doesn’t work. It harms women’s health and family health, and the health implications are costly.

Unfortunately, the prevailing approach in American culture is to put the onus to improve women’s health outcomes on individual women. Yes, individuals have the agency to improve their health, but only within the constraints of their environments.

The prevailing message to American mothers is that to improve their health they should find time to work out, relax, reduce stress, and take time for themselves. Advice suggests that this can be accomplished by asking for help or practicing yoga. However, individuals can’t pursue solutions to lessen stressors and improve health when the environment they operate within makes pursuit of available “solutions” near impossible. For example:

- Without paid leave, 25% of mothers return to work within two weeks of giving birth, when most are still bleeding.

- Most mothers are offered one postpartum visit six weeks after leaving the hospital, and a 2022 meta-analysis indicates that a substantial proportion of women don’t attend. According to the ACOG, 40% opt-out of the visit.

- Unpaid labor is associated with mental health distress. In the U.S., women perform 62% of the unpaid labor, with women performing a daily average of 4.5 hours of unpaid labor to men’s 2.8 hours.

- Childcare is unaffordable in 98% of U.S. counties, based on HHS’s definition of affordability.

- Parents of young children are hit especially hard, with 59% stating they had to cut back on work hours, or leave a job, due to the inability to find reliable and affordable childcare.

In an environment that doesn’t guarantee any paid leave, offers limited access to care after birth, disproportionately relies on women to provide unpaid labor, and offers minimal access to high-quality and affordable childcare, mothers can’t solve health disparities alone.

What Do These Health Disparities Look Like in the Healthcare Industry?

Moving from broad statistics and cultural root causes, let’s look at the healthcare industry, specifically. Healthcare organizations have a keen interest in improving maternal health given that women make up 77.6% of the healthcare workforce, 86% of nurses are women, and many of them are parents.

Looking at workforce health, just under half of physicians are burnt out, 56% of nurses are as well, and 64% of nurses feel immense stress due to their job. Burnt out employees aren’t as productive, and they are more likely to leave their roles. Additionally, mental health issues can cause or exacerbate physical health issues, leading to lower productivity and higher healthcare costs.

How Can Healthcare Entities Lead the Way in Improving Maternal Health?

Given the healthcare industry’s reliance on a predominantly female workforce, many of whom are also parents, healthcare entities may have the biggest impact on maternal health if they focus on improving their employees’ health.

There are a number of levers at their disposal, and no one-size-fits-all solution. Therefore, recent research suggests the best way to improve maternal health — and truly that of all employees — may be to provide a suite of services or offerings. A key one to consider is childcare support, given its role as a stressor and thus a root cause or exacerbation of physical and mental health issues.

There is a growing body of evidence that childcare is a major stressor for employed mothers. And some even consider childcare to be preventive healthcare. This begs the question, “If employers provide preventive healthcare benefits, should they also provide childcare benefits?” A recent study from BCG highlights that it benefits them to do so as the ROI on employers’ childcare benefits ranges from 90-425%.

While no single, employer-led solution will fix the national maternal health crisis, or the associated childcare crisis, healthcare employers have the power to reduce the stress their parent-employees feel, and therefore, to improve health outcomes and companies’ bottom lines. A lengthy list of options is available: Employers can provide on-site care, childcare stipends, flexible work hours to align with the hours care is available or children are in school, shortened work hours, a culture of respect for caregiving, etc. What’s critical is finding the right fit for each organization.

Identifying the Best Fit To Improve Health

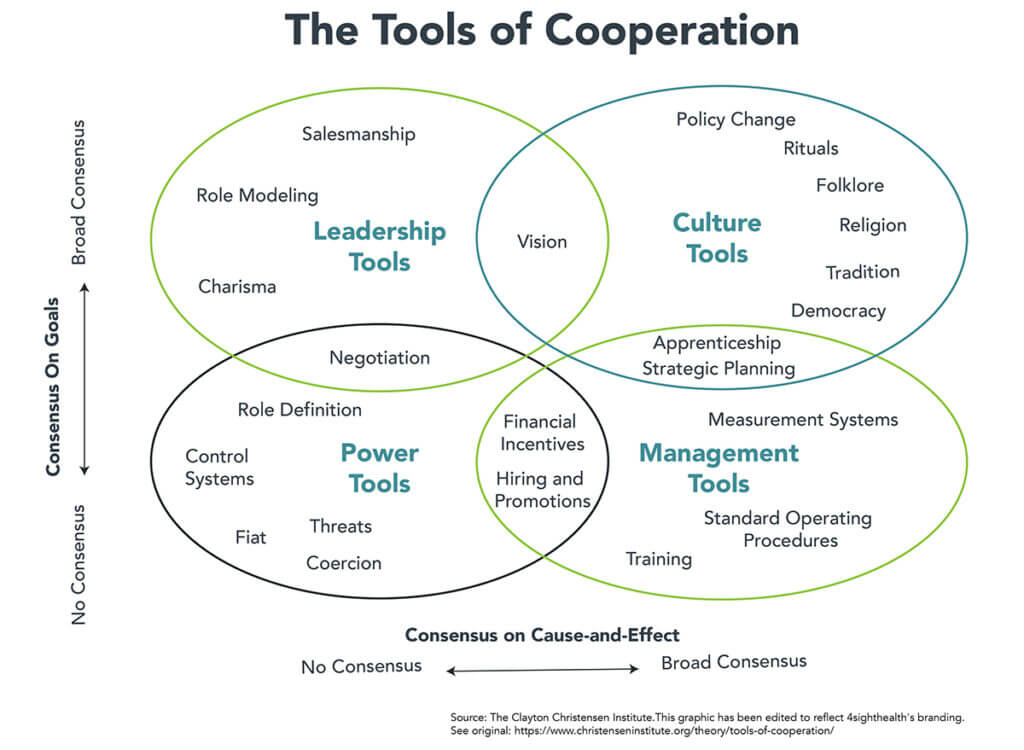

To determine the right fit for their organization, leaders can leverage the Tools of Cooperation, depicted below. It’s critical to understand that specific tools work in specific situations, so leaders must understand where their organization falls on the framework.

The vertical axis measures the extent to which the people involved agree on the goals or desired outcome. The extent of agreement can range from none (at the bottom) to complete agreement (at the top). A healthcare organization committed to improving maternal health for employees would be at the top.

The horizontal axis measures the extent to which the people involved agree on cause and effect (i.e., how to achieve the goals). Strong agreement (on the right-hand side) implies a shared view of the processes that should be used to get a particular outcome. Conversely, little agreement on how to achieve an outcome places an organization on the left-hand side. Because we don’t yet have consensus on the best approach to improve maternal health, most organizations are located on the left-hand side of the diagram.

Therefore, Leadership Tools, such as vision and role modeling, are available as levers for change when an organization has consensus around the goal of improving maternal health while improving their bottom line but some uncertainty on the best pathway to achieve the goal. In this situation, healthcare leaders can test one or a variety of solutions suggested above to reduce maternal stress and improve physical and mental health outcomes.

What’s key is for healthcare leaders to commit to improving maternal health and to understand that the workplace benefits they provide and the culture they create have a direct impact on health outcomes.

Employed mothers, and especially our caregiving workforce, are crushed under the weight of a system that doesn’t support their well-being. Healthcare leaders have an opportunity — and an obligation — to change this status quo. Improved health is a critical outcome, but investments in employee health can also yield improved productivity, greater employee retention, and better bottom lines. And right now, U.S. healthcare desperately needs all of these.