December 14, 2021

Burda on Healthcare: Patient Stories from the Front Lines Tell of a Healthcare Capacity Problem

One of the great myths about the healthcare system in the U.S. is that anyone can see a doctor or get the care they need any time they want if they have health insurance. There’s no waiting in our market-based, pluralistic system for medical care, whether it’s for an acute or chronic condition.

That myth is a big reason that we cling to our current system rather than moving to a government-run, single-payer system in which people, so we’ve come to think, are forced to wait days, weeks, months or even years for care that we can get this afternoon here in the U.S. if we need it. Communists!

I support a market-based, pluralistic healthcare system, and I oppose a government-run, single-payer healthcare system for a lot of reasons that I won’t go into here. But the idea that we don’t wait for care here, and you have to wait for care there, is a total joke. Unless you can afford to belong to a concierge medical practice, get in line, comrade.

Let me give you three recent examples in which the lack of capacity in our system resulted in one of my family members or friends delaying care. I won’t name them or reveal their relationship to me. I’ll just go with Patients A, B and C.

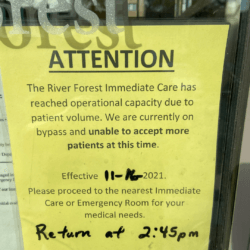

Urgent Care Goes On Bypass Status

Patient A is a Medicare beneficiary and is enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan. Patient A suffers from an arthritic knee, and the knee over the course of two weeks swelled up and made it painful to walk. So much so that Patient A asked me to take them to their primary-care physician that day. I said yes, but Patient A’s PCP was booked and referred Patient A to the PCP’s in-network urgent-care center.

We got there about 11 a.m. and, after Patient A registered to be seen, the nurse at the front desk told us that it would be about a 90-minute wait. Shortly thereafter, the urgent-care center went on “bypass” until 2:45 p.m. It wouldn’t registered any new patients until then, and anyone who did come in would be sent away.

We got there about 11 a.m. and, after Patient A registered to be seen, the nurse at the front desk told us that it would be about a 90-minute wait. Shortly thereafter, the urgent-care center went on “bypass” until 2:45 p.m. It wouldn’t registered any new patients until then, and anyone who did come in would be sent away.

I’ve heard of hospital emergency rooms going on diversion status because of a mass-casualty incident or overcapacity because of an influx of flu or COVID patients. But I’ve never heard of an urgent-care center going on diversion status.

During our 90-minute wait to be seen, at least a dozen people came in anyway, despite the sign on the door, and the nurse told them to come back at 2:45 p.m. or head to the ER if they couldn’t wait. One person said she fell at work, hit the back of her head on the floor, had a lump on the back of her head, felt dizzy and had a headache. Too bad. Try your luck later.

Win a Lottery to See a Specialist

Patient B has health insurance through their employer and is enrolled in a commercial HMO health plan. Patient B started suffering from unexplained headaches in June. After they became a daily occurrence, Patient B got a referral from their PCP in July to see a neurologist. The first available appointment to see any neurologist with the in-network practice was Dec. 28 — almost six months later.

Don’t worry, the practice’s office manager told Patient B. The practice frequently has cancellations, and Patient B can get on a waiting list for the first available appointment with any neurologist in the practice when another patient cancels. The practice would call when someone cancels, and if Patient B couldn’t make the new day and time, Patient B would not lose their place in line on the waiting list.

Don’t worry, the practice’s office manager told Patient B. The practice frequently has cancellations, and Patient B can get on a waiting list for the first available appointment with any neurologist in the practice when another patient cancels. The practice would call when someone cancels, and if Patient B couldn’t make the new day and time, Patient B would not lose their place in line on the waiting list.

In October, out of the blue, the practice sent Patient B a text message, informing them of an opening because of a cancellation. The text told Patient B that they had exactly one hour to claim the open spot and that they had to click on an embedded link to log into their patient portal to grab the appointment. In all caps, the text warned Patient B that the offer EXPIRES IN ONE HOUR.

Here’s the rub. The practice sent the text to Patient B about 5 p.m., or right before dinner. They didn’t see the text until about 7 p.m., or after making dinner, eating dinner and cleaning up after dinner. Not everyone is glued to their phone 24/7/365.

And when Patient B did see the text, it read like a phishing scam sent by text. Click here. You have one hour to claim your prize. Patient B ignored the text, thinking it was a scam only to realize that it was real after seeing a corresponding email in their inbox later that night. (Patient B showed me the text, and I would have deleted it, too.)

But by then, it was too late. The offer came and went with zero mention of it in Patient B’s portal. Unlike Patient B’s headaches, which are still there waiting for any neurologist to diagnose their cause.

The Doctor Has To Reschedule

Patient C also has health insurance through their employer and is enrolled in a commercial PPO health plan. Patient C has a number of chronic, albeit manageable, heart conditions — high blood pressure, high cholesterol, supraventricular tachycardia and a left-branch bundle block. After the left-branch, bundle block diagnosis, Patient C’s PCP in February referred them to a cardiologist.

Patient C’s first appointment with their new cardiologist was in April — two months after the referral. The cardiologist confirmed all the previous diagnoses, and agreed with the PCP’s treatment plan of monitoring, medications and lifestyle changes. Absent a significant change in their medical condition, Patient C and the cardiologist scheduled a regular six-month follow-up appointment for September.

Patient C’s first appointment with their new cardiologist was in April — two months after the referral. The cardiologist confirmed all the previous diagnoses, and agreed with the PCP’s treatment plan of monitoring, medications and lifestyle changes. Absent a significant change in their medical condition, Patient C and the cardiologist scheduled a regular six-month follow-up appointment for September.

Two weeks before the September appointment, the cardiologist’s practice called Patient C. We’re sorry, but the doctor has to reschedule your appointment because of an unexpected cardiology department meeting at the hospital. Unfortunately, his next opening isn’t until December. Again, he is very sorry he has to do this. Please accept his apology. I’m paraphrasing here based on Patient C telling me this story, which Patient C was only able to do because their medical condition didn’t deteriorate.

Now, you’d think that canceling an appointment at the last minute would get you the next available appointment as in later that same day or the next. Kind of like a restaurant giving you the next available table after they accidently gave away your first table. Not in this case. Patient C had to go to the end of the line because their doctor didn’t have any other open slots. Too busy. So sorry.

Limitations and Threads

Like a study in a peer-reviewed medical journal, let’s look at the “limitations” of these three anecdotes as being symptomatic of the entire industry. The situations could be explained by the people I know. It could be explained by their health plans and their provider networks. It could be the geographic area or market they live in. It could be the socioeconomic strata they’re part of. I realize there are millions of people who have worse medical problems and worse access problems than Patients A, B and C.

But I do believe that there are common threads that tie these three situations together, and one thread is capacity. There isn’t enough capacity in the current system to give these three people — and millions of people like them — the medical care they need when they need it. They have health insurance. But there are not enough urgent care centers, neurologists and cardiologists to treat them. That gap will only grow as the population ages and gets sicker, and we continue to underinvest in primary care, prevention and wellness — three paths that would reduce the need for acute care and medical specialists.

Another common thread is service. Come back later. We’re full. Click now to make an appointment or wait another three months. You’re bumped by a committee meeting. Deal with it. There’s a coldness in each story in terms of how the healthcare providers treated Patients A, B and C. The customer should always come first, especially in healthcare.

Maybe the two are related? You don’t have to be kind if you’re the only game in town and customers don’t have a choice of where to go.

Interestingly, Patients A, B and C mostly shrugged off what happened, as if they’ve come to expect this level of poor service from our healthcare system. Even the woman who fell at work and who urgent care sent away thanked the nurse at the front desk for her time as she weaved her way out the door and, I hope, made it to the ER safely.

We need more capacity. We need more competition. And we need a customer revolution in healthcare more than ever before.

Thanks for reading.