October 4, 2022

Pizza, Productivity and Healthcare

My favorite pizza joint at Colgate University was Peppe’s Ye Olde Pizza Pub. It’s still there. We used napkins to soak up the excess grease that pooled on the pizza before gobbling it down. We loved it. Peppe’s was also the first place I played the video game Pong. That certainly dates me!

I graduated in 1978. At the time, a slice of Peppe’s cheese pizza cost 50 cents. That same slice, made the same way, costs $2 in 2022, four times as much. This is my personal metric for inflation. I use it for calculating real (inflation-adjusted) costs as opposed to nominal cost.

Rounding up, a full year at Colgate, including tuition, room, board and expenses, cost $5,000 in 1978. That was a gargantuan sum. Minimum wage was $2.30 an hour. With student loans but no scholarships, I worked year-round and paid for 70% of my college education.

Today, Colgate’s full annual cost, including health insurance, is $86,000. Using my pizza-inflation metric, Colgate’s inflation-adjusted cost in 2022 is $21,500. That is more than four times greater than the comparable 1978 cost!

Despite the beautiful campus and incredible buildings and its reputation for educational excellence, there’s no way a Colgate education is worth four times what it was in 1978. And there’s no way a student without a scholarship could come close to funding 70% of the approximate $350,000 four-year cost, even with ample student loans and well-paying part-time jobs.

The key word in the paragraph above is worth. Worth links productivity with value. In economic terms, increasing productivity creates value by stimulating wealth creation, wage growth and improved living standards. Value decline creates negative worth when prices increase without a corresponding increase in productivity. Healthcare leaders should take note. There’s correlation with higher education’s skyrocketing costs and diminishing relative value.

Productivity and Healthcare

Before examining healthcare’s relative value, let’s first consider the fundamental relationship between productivity and value creation. The website for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has a short video that explains the basic concepts underlying labor productivity. The video uses a fictitious birdhouse builder named Beth to illustrate how productivity statistics measure the relationship over time between inputs (materials and labor) and outputs (in this case, birdhouses).

At first, Beth makes one birdhouse per hour. Becoming more efficient, she increases her per hour birdhouse production to two, doubling her labor productivity. Higher productivity enables Beth to earn more money for the same effort or earn the same amount of money by working less. Either way, Beth’s economic wellbeing (i.e., standard of living) improves. The video ends by correlating Beth’s experience to the broader economy: “Similarly, the standard of living for the country as a whole depends on improvement in overall productivity. Historically, productivity growth has led to higher wages for workers and higher profits for businesses.”

A college education has worth because it imparts knowledge, teaches new skills and expands an individual’s network of contacts. This not only enriches individuals’ lives, but also increases their productivity, market value and income potential.

A college education has worth because it imparts knowledge, teaches new skills and expands an individual’s network of contacts. This not only enriches individuals’ lives, but also increases their productivity, market value and income potential.

The skyrocketing cost of a college education, however, has diminished its relative value. Paying more (remember the pizza productivity metric) for a college education requires young people today to work longer and harder to match their parents’ standard of living. In this sense, the rising cost of a college education has become a drag on the overall U.S. economy and diminishes its aggregate human potential.

The same logic applies to healthcare. In 1978, the Health Care Financing Administration (the precursor to CMS) reported that the United States’ national, per-capita healthcare expenditure was $863.

CMS estimates that the per-capita 2022 healthcare expenditure will be $13,591. Using my pizza-inflation metric, the inflation-adjusted, per-capita cost would be $3,398. Like higher education, healthcare costs today are about four times greater than their inflation-adjusted 1978 cost.

Despite whizbang medical technologies, palatial care centers and breakthrough drugs, America is not four times healthier today than it was in 1978. By some health measures, including incidence of chronic disease, we’re far less healthy. The healthcare industry has gotten very good at enabling sick people to live longer. It has not improved our ability to live longer, healthier, more productive lives.

Waste Not, Want Not

The United States is currently in a prolonged productivity slump. Annual productivity growth has averaged less than 1% since 2011. This compares with a long-term average rate of 2.1% in annual productivity growth.

The sub-1% growth rate since 2011 includes a dismal 6% drop in productivity during the first half of 2022. Given the lack of current productivity improvement, it is unlikely that the United States can grow its way back to higher living standards any time soon. Spiking inflation reflects this unhappy economic reality.

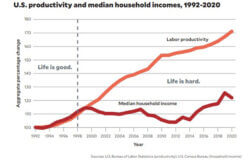

Historically, increases in median household income (MHI) paralleled improvements in labor productivity. Beginning around the millennium, however, MHI stagnated as productivity continued its upward march (see the chart). Life has gotten harder. This productivity-income divergence fuels political anger on the left and right. Despite the recent supply-driven uptick in wages, Americans today are working harder than ever but have less to show for their efforts.

Healthcare expenditure has contributed significantly to this widening gap between labor productivity and MHI. A commercial health insurance policy for a family (employer and employee contribution) cost 14.2% of MHI in 1999. By 2021, that ratio had grown to 32.7%.[2]

If the cost of a family health insurance policy had remained 14.2% of MHI in 2021, all other things being equal, the average family’s income would have increased from $67,994 to $80,529. This $12,535 jump would have closed 60% of the productivity-income gap. American pocketbooks would be fuller, and American spirits would be brighter. In a macroeconomic sense, spending less on healthcare with the same or better outcomes would free up enormous resources to pay workers more money, invest in more productive industries and address vital societal needs. What could that look like?

In a macroeconomic sense, spending less on healthcare with the same or better outcomes would free up enormous resources to pay workers more money, invest in more productive industries and address vital societal needs.

In a landmark 2012 JAMA article, Donald Berwick and Andrew Hackbarth estimated that 20% to 46% of total healthcare expenditures constitute waste.[3] Applying these percentages, waste now accounts for between $900 billion and $2.7 trillion of CMS’s projected $4.5 trillion national healthcare expenditure for 2022.

Eliminating healthcare waste is a logical path to a better, more productive life for all Americans. The savings could buy pizzas and a whole lot more for everyone in the country. That’s why HFMA’s focus on improving cost-effectiveness of health is such a just and noble cause. Let’s get it done together!

Sources

- Cheney, C., “CMS: Projection: Healthcare spending expected to reach $6.8 trillion by 2030,” HealthLeaders, March 28, 2022.

- Data sources: Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts, 2013-2021, and Employer Health Benefits Survey, 1990-2012; U.S. Census Bureau; and Sentier Research, House Income Trends June 2018 Report, July 2018.

- Berwick, D.M., and Hackbarth, A.D., “Eliminating waste in U.S. health care,” JAMA, April 11, 2012.