December 12, 2016

The Rise and Fall of Academic Medicine: AMC Competitiveness in Post-Reform Healthcare

Rome wasn’t built in a day and didn’t collapse overnight. After centuries of growth, prosperity and domination, the Roman Empire began a long slow decline at the peak of its territorial expansion in 117CE. Internal conflicts, administrative complexity, and wasteful consumption made Rome vulnerable to external attacks and led to the overthrow of its last emperor in 476CE.

Rome’s legacy survives through its cultural heritage and history. It provides a powerful example of what can happen to dominant institutions that ignore internal contradictions and resist pressures for constructive change. In healthcare, Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) ignore Rome’s lessons at their own peril.

Traditional AMCs have shaped U.S. healthcare delivery for over a century. Johns Hopkins established the nation’s first AMC in the 1890s modeled on research-oriented German institutions.

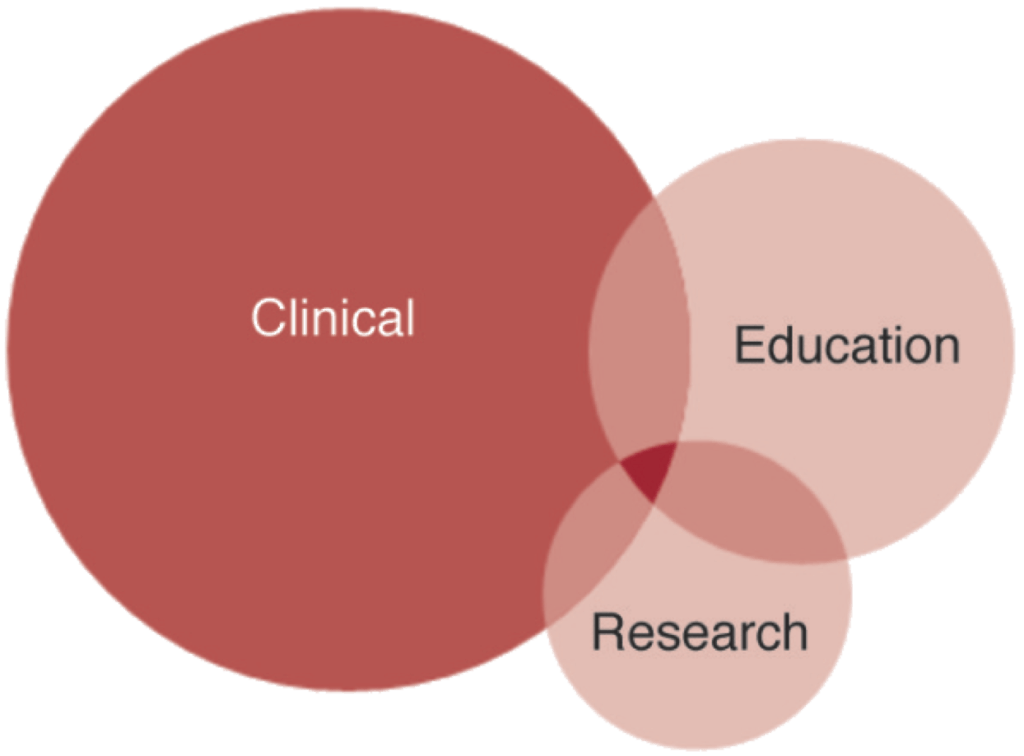

That business model combines clinical care with medical education and research. It remains largely intact today. Under societal pressures for more integrated, patient-centric and cost-effective healthcare services, AMCs struggle to fund their academic research and education missions.

Burdened by unwieldy governance, internal conflicts and high operating costs, AMCs find it increasingly difficult to compete against more nimble providers. They lack transparency in care outcomes, quality metrics, prices and customer experience. Many AMCs are finding it more difficult to justify the premium pricing and expansive cost-shifting that sustain their operations.

To remain vital, AMCs must meet marketplace service demands for excellent clinical care while supporting productive medical training and research. Traditional operating models are likely not up to the challenge. It’s time for introspection, honest assessment, new thinking, and strategic repositioning.

Venerable and Vulnerable

Academic medicine is vital to American healthcare. The U.S. has approximately 130 AMCs with direct ties to medical schools. These medical enterprises have diverse operating profiles that reflect their individual histories and market circumstances. Together, they provide 20% of the country’s care and 40% of its charity care.[1]

AMCs operate 60% of the nation’s Level 1 trauma centers, treating the most difficult cases. They annually graduate 17,000 doctors and train over 30,000 medical residents while conducting the majority of NIH-funded (National Institutes of Health) research.

AMCs have overlapping missions, multiple revenue sources and intricate subsidy arrangements. To fund medical education and research, AMCs receive public and private funding, clinical care subsidies and philanthropy.

Medicine is the single profession that combines education, basic research and business operations under one umbrella organization. Architecture schools don’t design buildings. Business schools don’t manage corporations. Law schools don’t operate law firms. Public policy schools don’t run governments.

By contrast, many AMCs actually manage clinical operations out of medical schools. Coordinating medical education, medical research and clinical care delivery within one academic framework led management guru Peter Drucker to describe academic medical centers (AMCs) as “the most complex organizations ever created.”[2] Drucker did not intend this as a compliment.

The academic model becomes even more complex when AMCs affiliate with networks of community hospitals and physicians. Typical physician debates over protocols, costs, referrals and capital investment often intensify.

Despite the complexity, AMCs are major enterprises. They have iconic brands and enjoy widespread public support. Underlying the AMC’s current business model, however, are tough operating realities:

- A high percentage (e.g. 80%) of AMC care could be provided in lower-cost community hospitals.

- PwC (formerly Price Waterhouse Coopers) research finds only 22% of consumers are willing to pay more for AMC care.[3]

- According to the Dartmouth Atlas, AMCs are often the most aggressive providers of high-cost, end-of-life care. Faculty practices (e.g. UCLA) generally have higher end-of-life care costs than group practices (e.g. Mayo Clinic).[4]

- Most AMCs receive poor quality scores from independent rating systems, such as the Medicare’s “star” ratings, The Joint Commission, and Leapfrog.

- AMCs confront significant state and Federal funding cutbacks for Medicare, Medicaid, indigent care and medical education.

- Despite an infusion of stimulus funding, NIH research funding has plateaued and is likely to decline.

Sub-titled “Strategies to Avoid a Margin Meltdown”, a 2012 PwC Health Research Institute report highlighted AMCs’ revenue, quality and governance challenges. It concluded, “up to 10% of traditional AMC revenues are at risk.”[5]

For AMCs with tight operating margins, this could be catastrophic. PwC recommended improving clinical outcomes, integrating into larger care networks, expanding telemedicine, becoming an “information hub” and enhancing translational research.

Efficient markets correct supply-demand imbalances. In true value-based healthcare, purchasers reward providers that deliver appropriate care in the lowest-cost settings. American consumers want the high-quality care AMCs offer without their high prices. It would be foolish to expect otherwise.

Masters in Misalignment

AMC ownership and governance structures have become impediments to market responsiveness, agile decision-making and robust capital formation strategies. This is particularly true in university-owned AMCs. About one third of AMCs are wholly-owned by universities.

Misalignment starts with governance and cascades throughout all academic and clinical activities. University boards are usually large, philanthropically oriented, lack healthcare expertise and politicized. They tend to focus on priorities that improve rankings, enrollment and research dollars.

In many cases, AMCs constitute over half of its university-owner’s revenues and a disproportionate share of its financial risk. Many university leaders question their institutional ability to manage the risks of academic medicine at a time of profound industry change.

AMC’s decentralized governance model grants department chairs significant autonomy to manage their specialties (e.g. cardiology). This leads to breakthrough innovations, but complicates care coordination. It is difficult to get agreement on protocols, costs and referrals let alone capital investments and go-to-market strategies.

Perverse incentives reward counter-productive behaviors. Clinical departments promote faculty physicians and award tenure based on research, publication, and external peer recognition, not internal clinical performance.

Likewise, physician income reflects external benchmarks driven by fee-for-service payment. In academic settings, more and higher reimbursement is always better irrespective of value.

These business realities often create inherent conflicts of interest between physician behaviors, patient needs and enterprise goals.

To the marketplace, traditional AMC governance and operating models are anachronistic, inefficient and high cost. Many question their sustainability and relative societal value. In response, AMCs’ leaders need to address the following existential questions:

- Why are we in business?

- Who are our customers?

- How do we create and deliver value to the marketplace?

- Do our research and education programs address true societal needs?

Fiddling While Rome Burns

History does not look favorably on leaders who practice business as usual in the face of disruptive change. The paragon of blissful ignorance was Emperor Nero who fiddled while Rome burned.

Not all AMC leaders see their internal contradictions and market challenges as dire. Many operate comfortably from positions of market strength. They receive premium commercial payments to participate in health insurers’ care networks. They often view care management and population health as solutions in search of problems.

Even the growth of high-deductible plans does not faze them. The emergence of wrap-around insurance coverage for deductibles and co-pays reduces downward pricing pressures. Private commercial revenues feed ever-expanding investments in technology, facilities and revenue-generating surgeons.

To date, Americans generally have been willing to support and pay AMCs’ high prices, but it’s reckless to believe revenue growth can continue unabated and independent of market forces. Sunshine is a strong disinfectant. Pricing transparency will expose AMCs’ cross-subsidies. Most such subsidies began for the right reasons, but remain hidden and unjustified.

Enlightened AMCs will reduce clinical cross-subsidies and seek targeted financial support from payers and philanthropists for medical research and education. This will be painful. Hard cost-benefit discussions will replace pious declarations of societal and community benefit. AMCs that deliver measured and tangible societal benefit will prosper at the expense of AMCs that stonewall.

Which Road to Rome

Not all AMCs can continue as independent operations. Industry consolidation and repositioning are market-driven realities. Structural optimization can follow three different roads. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

Be A Consolidator

Consolidators grow through acquisition and service-line expansion. Consolidating AMCs buy other hospitals, health plans or community physician groups to integrate care delivery, but also to increase their negotiating leverage with payers. Payers need “consolidators” in their delivery networks, so they agree to premium prices for routine and specialty services.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), closely affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh, began its merger and expansion strategy in the late-1980s. Today, it is a $12.8B integrated operation with over 20 hospitals, 500 clinical locations, a health plan, and domestic and international commercial ventures. It is also not-for-profit.

UPMC is noteworthy in that the growth of its clinical enterprise not only gave it leverage in the marketplace, but those revenues also supported its academic mission and improved its standing in education and research.

In contrast, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Penn Medicine, and Partners Healthcare have engaged in consolidation strategies to maintain their positions as leaders in research and academic medicine.

Be A Network Builder

“Network builders” affiliate with other hospitals and physician practices in their markets to funnel patient volume into AMCs. Strategic network builders include the University of Michigan Health System, Emory Healthcare, and The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center.

While network builders avoid capital acquisition costs, they become vulnerable as markets shift toward value-based payment models. Network partners are less-likely to refer patients to high-priced AMCs when accountable for total care costs. Spot markets for tertiary care will emerge, and large community hospitals will expand their tertiary care services to compete against premium-priced AMCs.

As noted earlier, most AMC patient volume is non-tertiary and available in lower-cost community hospitals. Given their large physical plants, AMCs cannot survive providing only tertiary care.

Over time, AMCs must right size facilities to meet intrinsic demand for tiertiary care services and find lower-cost venues for routine care services. “Network building” AMCs that fail to improve their service models and reduce their cost structures risk being priced-out of their marketplaces.

Premium brands, such as the Cleveland Clinic, are exposing AMC vulnerability by offering efficient specialty care networks and low-cost second opinions outside their traditional service areas. Better coordinated care at lower prices deprives AMCs of profitable patient volume.

Join Another System

Some AMCs don’t have the market power necessary to expand through either acquisition or network building, so they relinquish autonomy and join more dominant systems.

Last year, the University of Arizona Medical Center agreed to a 30-year affiliation with Banner Health as part of Banner’s acquisition of the University of Arizona Health Network.

Under similar financial pressure, the University of Toledo College of Medicine signed a long-term affiliation agreement with ProMedica in 2015 because their University-owned medical center was not big enough to support the College of Medicine’s academic missions.

Reinventing Rome

The Ancient Rome was the “Eternal City” because its citizens believed other empires would rise and fall but Rome would always remain. For AMCs, Rome represents an eternal and ideal market position that enables advancing medical education and research while receving premium prices for routine services. Society pays and says, “Thank You.”

Of course, Rome’s complacency meant it never acknowledged or addressed the existential threats that ultimately caused its ruin. A more dynamic and “hungry” Rome could have adapted to new realities and prospered.

Evolution acknowledges market realities and adapts to them. In order to remain viable, AMCs must confront their existential threats, redesign their business models and deliver value to customers. In this way can AMCs prosper financially while meeting their educational and research missions.

Academic medicine is at an inflection point. American healthcare is evolving toward patient-centric care delivered in lower cost and more convenient settings. Large multi-hospital systems are encroaching into AMCs’ tertiary care business lines. It’s adapt or die time for most AMCs. They must do some or all of the following to remain relevant:

- Gain scale, either as a buyer or a seller

- Profitably deliver routine care at Medicare rates

- Make the education and research subsidies transparent. Become accountable and pro-active in seeking partners to fund mission-related activities.

- Separate clinical operations from academic activities, while still delivering learning opportunities “at the bed-side.” This functionally means operating the clinical enterprise independently from sponsoring university.

These strategies represent opportunities to preserve and pursue academic medicine within a more stringent post-reform operating environment. All successful enterprises evolve. Owning buildings is less important than delivering superior, efficient and convenient care services to patients.

Irrespective of organizational structure and ownership, AMCs create value through operating cultures that create knowledge, train practitioners and advance care delivery. These outcomes should be at the forefront of leaders’ thinking as they evaluate post-reform business strategies.

American healthcare needs this type of leadership now and forever.

Disclaimer:

The information contained in this report was obtained from various sources that we believe to be reliable, but we do not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Additional information is available upon request. The information and opinions contained in this report speak only as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. This report has been prepared and circulated for general information only and presents the authors’ views of general market and economic conditions and specific industries and/or sectors. This report is not intended to and does not provide a recommendation with respect to any security. Any discussion of particular topics is not meant to be comprehensive and may be subject to change. This report does not take into account the financial position or particular needs or investment objectives of any individual or entity. The investment strategies, if any, discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. This report does not constitute an offer, or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or other financial instruments, including any securities mentioned in this report. Nothing in this report constitutes or should be construed to be accounting, tax, investment or legal advice. Neither this report, nor any portions thereof, may be reproduced or redistributed by any person for any purpose without the written consent of Cain Brothers.

Cain Brothers is a member of SIPC. © 2016 Cain Brothers and Company, LLC

CO-AUTHOR

DAVID MORLOCK

DAVID MORLOCK

David Morlock joined Cain Brothers in 2016, as a Managing Director in the Health Systems Group. With over 25 years of experience as a health system executive, Mr. Morlock’s track record includes strategy development, mergers and acquisitions, affiliation agreements, joint ventures, major capital investments, and other unique arrangements tailored to meet the needs of healthcare organizations’ specific circumstances.

Cain Brothers is a pre-eminent investment bank focused exclusively on healthcare. Our deep knowledge of the industry enables us to provide unique perspectives to our clients and is matched with the knowhow needed to efficiently execute the most complex transactions of all sizes.www.cainbrothers.com

[1] “Academic Medicine: Where Patients Turn for Hope,” AAMC website: https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Academic%20Medicine%20Where%20Patients%20Turn%20for%20Hope.pdf

[2] http://www.creative-healthcare.com/blog/2014/11/, November 2014

[3] “The future of the academic medical center: Strategies to avoid a margin meltdown”, PWC – Health Research Institute, February 2012, pg 5: http://www.aahci.org/Portals/1/AIM_Best_Practices/Financial_Alignment/The_Future_of_the_Academic_Medical_Center_Strategies_to_Avoid_Margin_Meltdown.pdf

[4] “Tracking Improvement in the Care of Chronically Ill Patients…”, Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice – A Report of the Dartmouth Atlas Project, June 2013: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/EOL_brief_061213.pdf

[5] “The future of the academic medical center: Strategies to avoid a margin meltdown”, PWC – Health Research Institute, February 2012, pg. 4: http://www.aahci.org/Portals/1/AIM_Best_Practices/Financial_Alignment/The_Future_of_the_Academic_Medical_Center_Strategies_to_Avoid_Margin_Meltdown.pdf