April 28, 2022

Separate And Unequal (Part 1): Healthcare’s Profound Maldistribution of Facilities

Ready. Set. Stumble.

As part of its announcement of payment guidelines for FY 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched six initiatives to advance health equity and improve maternal health outcomes within hospitals. These initiatives are central to the Biden Administration’s commitment to “improving care for people and communities who are disadvantaged and/or underserved by the healthcare system.”

The initiatives do the following:

- Introduce three new health equity reporting measures that emphasize healthy multipliers (i.e., social determinants).

- Introduce two new, maternal-health reporting measures that seek to reduce low-risk Cesarian deliveries and severe obstetrics complications.

- Create a “birthing-friendly” hospital designation.

No one can question the Biden Administration’s commitment to health equity. The CMS announcement occurred the same week that Vice President Harris convened a first-of-its-kind White House meeting to promote a “whole-of-government” program to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. That session was part of the Administration’s “historic Call to Action” announced by Harris in December 2021 “to improve health outcomes for parents and their young children in the United States.”

While well intended, these initiatives will increase hospitals’ already high reporting burden without improving health access and outcomes in meaningful ways. Acute chronic disease admissions primarily result from inadequate primary-care services. Likewise, maternal morbidity and mortality primarily result from inadequate prenatal care. Hospital admissions for these conditions provide expensive crisis care for high-risk patients. Poor outcomes are routine.

By focusing its regulatory interventions and political clout on acute admissions, the Biden Administration is missing the opportunity to intervene earlier at much lower costs to improve care outcomes and life quality. The right solutions are obvious but hard to implement.

Enhanced primary-care services can prevent or mitigate chronic conditions before they morph into debilitating disease. Effective pre- and post-natal care dramatically improves maternal and newborn health at birth, so mother and child can begin a more promising life together. They also dramatically reduce the number of low birth-weight babies and the need for high-cost neo-natal intensive care.

Under current payment models and regulatory policies, it is almost impossible to optimize health and well-being within impoverished neighborhoods. They lack adequate facilities and practitioners to provide these vital and basic primary-care services. At best, the CMS initiatives will marginally improve upon dismal care outcomes for medically underserved communities.

A West Side Story

Chicago’s west side illustrates the stark contrast between healthcare’s haves and have nots. West Suburban Medical Center sits on the west side of Austin Avenue which separates the low-income Austin neighborhood in Chicago from the affluent suburbs of Oak Park and River Forest. The Medical Center’s primary service area encompasses these three communities.

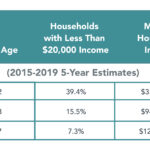

Despite their proximity, Austin and Oak Park/River Forest have starkly different demographic profiles (see chart below).

As an investment banker in the 1990s, I arranged rating agency reviews for West Suburban as part of a bond issuance process. The CEO’s presentation to the rating agencies included a slide that displayed the Medical Center’s clinic locations. West Suburban had dozens of clinics in Oak Park and River Forest. It had just one in Austin. I remember trying to imagine what Jesse Jackson’s reaction to that slide would have been.

Today, the Medical Center still saturates Oak Park and River Forest with medical facilities and practitioners but has no presence at all in Austin. Despite a much larger population than Oak Park/River Forest, Austin has only four primary-care clinics to provide basic care services to its residents. The facilities operate during normal business hours and don’t provide emergency services. Two are open Saturday mornings. None operate on Sundays.

Given their limited hours and capabilities, these clinics provide woefully inadequate medical access for Austin’s residents who suffer disproportionately from heart disease, diabetes and cancer. Consequently, they do not receive the enhanced primary care services they require to manage their chronic conditions. The result is deadly. Life expectancy in Austin is just 72 years

Not surprisingly, pregnant women in Austin often fail to receive adequate pre- and post-natal care. As a consequence, Austin has one of Chicago’s highest maternal morbidity rates with well over 100 cases per 10,000 deliveries. Low birthweight deliveries are routine. Challenged new mothers and their babies too often begin life together in jeopardy.

While West Suburban does not actively market its services in Chicago, desperate local residents flood the Medical Center’s emergency room when health emergencies strike. According to the Illinois Hospital Report Card, low-income Medicaid, charity and self-pay patients represent almost half of West Suburban’s inpatient case mix. Many, perhaps most, of these Medicaid patients are Austin residents suffering from treatable chronic conditions.

Health status across Austin Avenue in seems other-worldly. Oak Park/River Forest residents live longer, healthier lives. With abundant healthcare access, an educated population and readily available social services, chronic disease is much less prevalent, and its onset occurs later in life. Healthy births are routine.

Life expectancy in Oak Park/River Forest is a robust 83 years. Residents live a full eleven years longer than their Austin neighbors. This “death gap” is unacceptable, preventable and not unique. Most metropolitan areas in the United States have similar death gaps within their borders. They represent a profound failure of U.S. health and social policy and care delivery.

Separate and Unequal

The reason for the profound maldistribution of healthcare facilities in west Chicago and around the country is simple and inhumane. Healthcare providers, like West Suburban, locate their facilities and practitioners where they can attract the greatest number of high-paying, commercially-insured patients.

Hospitals’ organizational imperative to optimize revenues and profits overwhelms their humanitarian responsibility to treat all patients equitably. Excessive chronic disease, maternal complications and premature death result.

Compounding healthcare’s facility maldistribution challenge is that hospitals serving low-income urban and rural communities are typically older, less resourced and have poor quality ratings. They consume vital healthcare resources without providing the enhanced primary, maternal and social care services their residents require to live healthier, more productive lives. Yet, closing or repurposing such underperforming facilities usually triggers political backlash.

Compounding healthcare’s facility maldistribution challenge is that hospitals serving low-income urban and rural communities are typically older, less resourced and have poor quality ratings. They consume vital healthcare resources without providing the enhanced primary, maternal and social care services their residents require to live healthier, more productive lives. Yet, closing or repurposing such underperforming facilities usually triggers political backlash.

The Biden Administration’s goal of making hospitals more accountable for health equity and maternal health isn’t necessarily bad. It just won’t do much to achieve the Administration’s desired outcomes.

The United States has the capacity but lacks the resolve to reallocate healthcare resources in ways that equalize care access, enhance health status and reduce death gaps. This requires fundamental payment reform, less specialty care and enhanced primary care services. This would enable the healthcare system to address the root causes of disease, not its biproducts.

Part 2 of “Separate and Unequal: Overcoming Healthcare’s Profound Facilities Maldistribution” tackles this meaty and important policy challenge.