October 14, 2021

State-Based Marketplaces 2.0 (Part 1): The Coming Expansion in Access, Affordability and Value

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) survived its third challenge at the Supreme Court on June 18, 2021, by a 7-2 vote, signaling that Obamacare is here to stay. With a divided Congress and a Biden administration challenged by multiple urgencies, there is little hope for national legislation to address healthcare’s access, cost and quality deficiencies comprehensively.

Despite this lack of dramatic progress or sweeping change at the federal level, reformers need not lose hope. Quietly, state-based marketplaces are making health insurance provision more accessible, affordable and effective.

A Biden Administration’s executive order signed in January, 2021, reopened the federal health insurance marketplace to individuals seeking to purchase or modify health insurance policies. [1] The fifteen state-based marketplaces (SBMs) followed suit by enacting their own versions of this special enrollment period.

The Administration’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, enacted on March 11, 2021, includes a narrow but powerful provision that temporarily grants premium subsidies to higher-income Americans and reduces premium costs for lower-income Americans. [2] The “Build Back Better Act” currently moving through the House of Representatives would make these subsidies permanent. It would also provide funding for more experimentation with state-based health insurance affordability programs.

These new policies align with measures undertaken by many SBMs during the past eight years to improve the quality, affordability, and marketability of their health insurance offerings. In this decentralized, real-world way, SBMs have operated as experimental policy laboratories to assess programming modifications for stabilizing local markets, expanding consumer choice, increasing access to vital healthcare services, and lowering premiums.

Successful SBM innovations have demonstrated that insurance marketplaces can adapt and thrive by responding to consumer preferences. By expanding to more states, adopting proven remedies, and more effectively overseeing plan sponsors, SBMs can provide even more Americans with access to the affordable health and wellness services they need.

The Evolution of State-Based Marketplaces

Enacted in 2010, the ACA introduced guidelines and provided start-up funding for SBMs. The legislation’s aim was to create affordable health insurance options that Americans lacking health insurance coverage could purchase on market-based exchanges.

Inspired by Massachusetts healthcare reform (aka “Romneycare”), the framework built on non-ACA purchasing cooperatives offering “small group” health insurance plans. The new marketplaces enabled individual consumers to purchase ACA-compliant health insurance coverage online. The ACA also provided income-based subsidies for qualified enrollees.

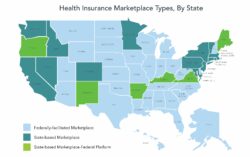

Source data: Kaiser Family Foundation

The ACA’s designers believed that most states would develop their own marketplaces. They established HealthCare.gov, a federally operated alternative, to provide access to ACA plans in states that chose not to create SBMs.

Political resistance impeded widespread adoption of SBMs at the outset. Yet, SBMs have not only thrived in the years since, they are now poised to expand. Kentucky, Maine, and New Mexico are launching their own state-run marketplaces this fall for operation in Plan Year 2022. Others, including Virginia, will likely follow.

SBMs operate as marketplaces for insurers to compete in offering plans that meet ACA-regulated standards. SBMs also promote enrollment, pool risk to lower premiums, and facilitate comparison shopping.

A Critical Safety Net

Including HealthCare.gov, 12 million consumers have enrolled in market-based plans for calendar year 2021, an increase of 600,000 from 2020. Over 3.8 million of the 12 million enrolled through SBMs. The vast majority of enrollees (including 88% of the consumers enrolled through HealthCare.gov) receive some financial assistance in the form of subsidies. [3]

Despite the increased enrollment, more than 30 million Americans remain uninsured [4] and 43.4% of the population has inadequate health insurance coverage. [5] The number of uninsured people in America declined significantly with implementation of the ACA in 2014, then began to rise in 2017 as the Trump Administration reduced support for enrollment.

The pandemic-related economic shutdown seemed likely to balloon the ranks of the uninsured. Instead, employer-based coverage largely held and many who found themselves suddenly uninsured secured coverage through Medicaid or marketplace health plans.

The extension of the open enrollment period and the enhanced subsidies have facilitated enrollment in SBMs and HealthCare.gov this year. For an estimated one million people, marketplace health plans provided a critical safety net. [6]

Continued Growth & Improvement

Despite the charged political debate since the ACA’s passage, SBMs have shown great promise and resilience. Many SBMs have adopted targeted solutions to make health plan premiums more attractive and affordable. Some have enabled consumers to shop and compare plans more easily. Others have included reinsurance, enhanced subsidies and/or individual mandates that strengthen the risk pool and help to reduce prices.

Different approaches among states can lead to drastic differences in the affordability and attractiveness of health plan offerings. Minnesota’s decision to offer reinsurance to insurers with health plans on its SBM lowered its 2021 monthly benchmark rate to $292. Across the state line in Wisconsin, the monthly benchmark rate jumped to $782. The 2021 national average benchmark premium is $443 per month. [7]

Analysts, administrators and policy makers are studying these different approaches to better understand the factors influencing elasticity of demand in state and federal marketplaces. The results can be striking.

One study showed that the existence of individual mandates in state-based marketplaces increases the likelihood that individuals will purchase health insurance policies, regardless of financial penalties. [8] Other studies confirm that individual tolerance for higher premiums increases with a greater perceived need for health insurance, as occurs with factors such as poor health and older age. Such priorities increase demand for health insurance and reduce price elasticity.

That said, a standardized menu of affordable options increases consumer sensitivity to price. [9] States can adopt an evidence-based approach by using this type of knowledge to tweak program offerings and make them more attractive to marketplace consumers.

SBMs monitor each other’s strategies closely, often adopting innovations appropriate to local needs. By using an evidence-based approach, they can make their offerings even stronger. Progress will also stimulate interest in other states for developing their own marketplaces. As noted above, SBMs’ collective success has already influenced several traditionally red and purple states, including Kentucky, Maine, New Mexico, and Virginia, that are now implementing their own SBMs. [10]

With political headwinds now turning into tailwinds, SBMs are finding it easier to enact modest but practical structural improvements that can make their marketplaces even more robust and attractive. Growth will continue as more product offerings come to SBMs, consumers gain more choices, value-driven transactions increase, health outcomes improve and system-wide costs decrease.

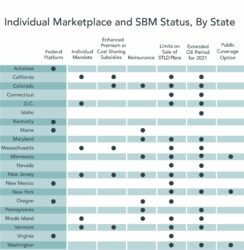

The table highlights several provisions adopted by states operating a state-based exchange. Of note, this table calls out which states have implemented an individual mandate – the primary “stick” states may use to drive enrollment – as well as enhanced premium or cost-sharing subsidies, the main “carrot.” In addition, the grid notes which states have extended their SBM’s open enrollment period for 2021, among other consumer protections.

For additional detail, please see a summary of these and many other state actions to support access to health insurance coverage from the Commonwealth Fund.

Conclusion: Local Solutions Advancing Meaningful Reform

The ACA gives states the flexibility to implement SBMs and encourage private sector participation. The federal government is responsible for establishing coverage standards, financing subsidies, and operating the HealthCare.gov platform. But it faces some challenges when it comes to innovating.

By contrast, states can be nimble. They can tailor program offerings to meet market demands and dynamics. Factors influencing program design could also include the state’s urban/rural mix, the size of its employer base, the payer mix, social determinants of health, demographics and cultural attributes. This ability to accommodate market preferences and other factors validates the federalist approach that the ACA takes in granting SBM program design to the states.

This flexibility avoids the “one-size-fits-all” approach incorporated within the federally-run marketplace. By tailoring their SBMs to local circumstances, the states have become vital engines of experimentation and innovation for advancing the overall effectiveness of the nation’s healthcare marketplaces.

With enhanced program design and expansion to more states, along with support from the Build Back Better Act, SBMs are well positioned to serve as a catalyst for meaningful healthcare reform. Not all progress is revolutionary. As SBMs have demonstrated, evolutionary improvements in benefit design, enrollee engagement, risk management and outreach enable millions of American consumers to gain affordable access to high-quality care.

Read the next part of this series, State-Based Marketplaces 2.0 Part 2: Engines of Innovation, Competition and Consumerism here. Read the combined article here.

Sources

- Andrews, M. (2021, February 15). As Biden Reopens ACA ENROLLMENT, are you eligible to sign up or switch HEALTH PLANS? NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/02/15/967366282/as-biden-reopens-aca-enrollment-are-you-eligible-to-sign-up-or-switch-health-pla.

- Kliff, S. (2021, January 16). One sentence In Biden stimulus Plan reveals his health care approach. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/16/upshot/biden-obamacare-stimulus.html; American rescue PLAN Act funding

breakdown. NACo. (2021, July 29). https://www.naco.org/resources/featured/american-rescue-plan-act-funding-breakdown - HEALTH INSURANCE MARKETPLACES 2021 OPEN ENROLLMENT REPORT. CMS.gov. (n.d.).

https://www.cms.gov/files/document/health-insurance-exchanges-2021-open-enrollment-report-final.pdf. - Finegold, K., Conmy, A., Chu, R. C., Bosworth, A., & Sommers, B. D. (2021, February 11). TRENDS IN THE U.S. UNINSURED

POPULATION, 2010-2020. HHS.gov. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/265041/trends-in-the-us-uninsured.pdf - Collins, S. R., Gunja, M. Z., & Aboulafia, G. N. (2020, August 19). U.S. health insurance coverage in 2020: A looming crisis in

affordability. Health Coverage Affordability Crisis 2020 Biennial Survey | Commonwealth Fund.

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/aug/looming-crisis-health-coverage-2020-biennial. - COVID enrollment period. ACA Signups. (n.d.). https://acasignups.net/covid-enrollment-period.

Minemyer, P. (2021, May 24). Average benchmark premiums for ACA exchange Plans decline again IN 2021: Report.FierceHealthcare.

https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payer/average-benchmark-premiums-for-aca-exchange-plans-decline-again-2021-report#:~:text=Average%20benchmark%20premiums%20for%20plans,fell%20by%201.7%25%20for%202021. - Saltzman, E. (2017). Demand for Health Insurance: Evidence from the California and Washington ACA Marketplaces. University

of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1140&context=hcmg_papers - Abraham, J., Drake, C., Sacks, D. W., & Simon, K. I. (2017, July 24). Demand for health insurance marketplace plans was highly

elastic in 2014-2015. NBER. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23597. - It’s worth noting that states that establish their own marketplaces can recapture the user fee that they must pay to the federal

government for participating in HealthCare.gov. This is a sizeable assessment that can save states millions of dollars. See:

Schwab, R., & Volk, J. A. (2019, June 28). States looking to run their own health insurance marketplace see opportunity

for funding, flexibility. States Looking to Run Own Insurance Marketplace See Opportunity | Commonwealth Fund.

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/states-looking-to-run-their-own-health-insurance-marketplace-see-opportunity.

This commentary also published in The Healthcare Blog on October 18 2021, here.