May 26, 2020

Understanding Despair, Capture and Profiteering in American Healthcare

In their recent book “Deaths of Despair,” Anne Case and Angus Deaton chronicle the rise of drug overdose, suicide and death by alcohol in the United States. Through their vivid writing with supporting statistics, they document a slow-motion catastrophe among vulnerable Americans in the grips of unremitting despair. Their American dream has become a nightmare.

COVID-19 has made that nightmare even worse. The pandemic has exposed the fault lines in American healthcare, disproportionately attacking and killing the poor, the already sick, the dispossessed and the elderly. The U.S. has 5% of the world’s population but has absorbed 30% of the world’s COVID deaths.

COVID-19 also has exposed the vulnerability of current transactional delivery models. Providers are bleeding red ink. Despite confronting the greatest healthcare crisis in over a century, healthcare companies laid off 1.4 million workers in April. Supply chain, data, logistics and communications systems have all failed in fundamental ways.

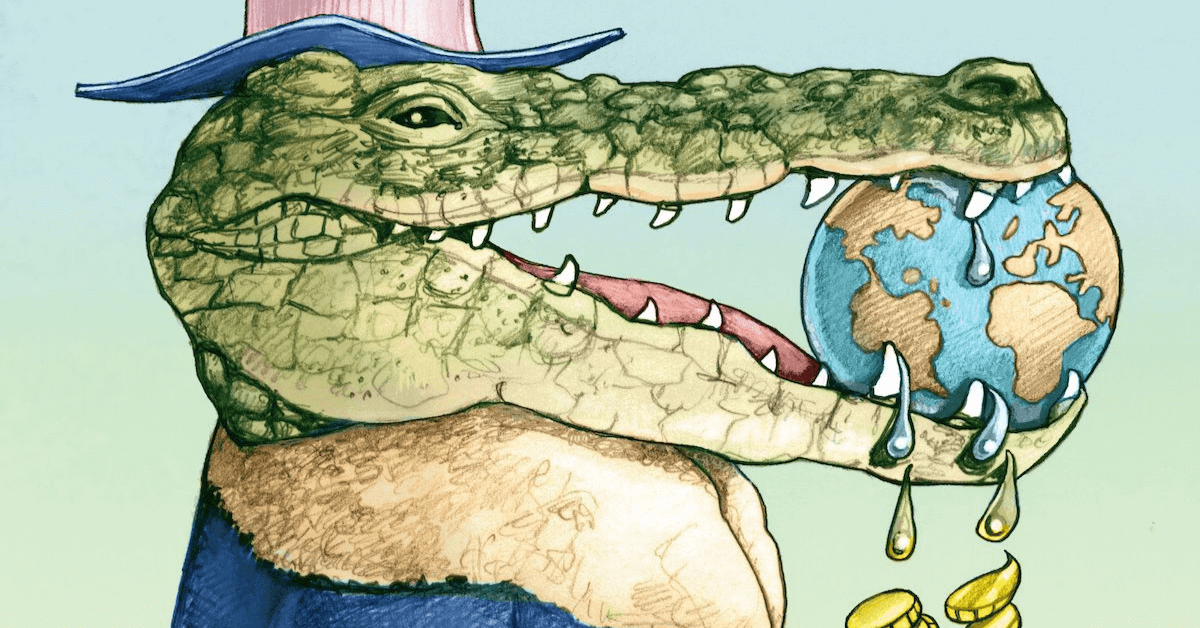

Current U.S. healthcare runs on rent-seeking and profiteering. More of the same will yield more of the same. Already a topic of intense political debate, reforming U.S. healthcare amid COVID -19 has become the paramount policy issue. It is an issue fraught with complexity and risks.

Beneficiaries of America’s Deaths of Despair

Case and Deaton argue that America’s epidemic of despair is multifactorial with causes woven through a number of our economic and social domains. I’m going to discuss one “cause” in particular. Chapter 13 of their book is named “How American Healthcare is Undermining Lives.”

The authors correctly note that American healthcare is the most expensive in the world but produces results, at least as measured by lifespan, that are significantly below countries that spend less per capita. One particular point the authors make is striking. They maintain that the US healthcare system efficiently redistributes wealth through “rent-seeking” from the working class to the wealthy.

Redistributing income and wealth upward from lower income and wealth populations is nothing new. Taxes on tobacco and alcohol fall disproportionately on the poor and working class, state monopolies on gambling – especially lotteries – even more so.

Economists term these “sin” taxes “voluntary” because consumers voluntarily purchase alcohol, tobacco and long-shot chances at greater wealth. While acknowledging their regressive nature, authorities argue that these taxes discourage destructive behaviors and support worthy causes, such as school funding.

Gaining economic “rents” is a means of wealth transfer that is imposed rather than “voluntary.” The economist Gordon Tullock described “rent-seeking” as “the expenditure of resources in order to bring about an uncompensated transfer of goods or services from another person to one’s self as the result of a “favorable” decision on some public policy.”

Rent-Seeking: the expenditure of resources in order to bring about an uncompensated transfer of goods or services from another person to one’s self as the result of a “favorable” decision on some public policy.

While there are a number of manifestations of rent-seeking in our political economy, lobbying is one of the most visible. Almost all aspects of American life engage lobbyists. Whether it is guns, forestry, agriculture, taxes, or telecommunications, there’s a lobbyist for that. By definition, lobbyists seek to improve their clients’ financial profiles by influencing governmental legislative and regulatory mechanics.

The healthcare industry annually spends over one-half of a billion dollars lobbying, employing a regiment of nearly 3,000 lobbyists. Basic economics would tell you that the healthcare industry’s investment in lobbying is paying big dividends. At a minimum, the “rents” benefit at least covers the cost of lobbying. In reality, lobbying generates a return multiple far beyond its cost. That return comes at the expense of American people.

Rent-Seeking and the American Politician

Healthcare’s complexity necessitates that members of congress rely on lobbyists for information regarding policy choices. I have heard members of Congress, in response to a policy description, say “That sounds good, but I’ll need to check with my lobbyists.” The possessive in that statement is particularly disturbing.

Slogans guide healthcare policy debates more often than substance. On the left of our healthcare politics, representatives passionately advocate for “Medicare for All” and “single payer” healthcare. Most could not survive more than a few probing questions about how those programs would affect the healthcare system and the economy at large.

On the right, the slogan of “free market” dominates without the acknowledgement or understanding of how “free market” healthcare would operate in the context of our already government-dominated payment system. And the right is loath to dismantle most of that payment system.

Probably the worst contemporary example of the operation of a rent-seeking (and profiteering) is the opioid crisis. Pharmaceutical companies produced and sold massive quantities of highly addictive painkillers, aided by misleading information about addictive qualities. Complicit physicians prescribed, pharmacists filled orders, and regulatory agencies, neutered by pharma lobbying, looked the other way.

At the height of the crisis, the numbers went from staggering to absurd. Between 2007 and 2012, Big Pharma shipped twelve million hydrocodone tablets to one small town in West Virginia — Kermit pop. 400. Influence peddling by lobbyists paved the way for Big Pharma to make big profits. They did their jobs exceptionally well while millions of despairing Americans suffered, and hundreds of thousands died.

Beyond paid lobbyists, healthcare overflows with rent-seeking practices. While leading the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), I received calls almost daily from members of congress looking for a specific act to advantage or “fix” a constituent’s problem. Two calls still stand out.

- The first came from a congressman in the southeast. A company in his district was undertaking a risk-based demonstration project aimed at disease management in difficult populations. The project was failing badly, and the company owed CMS over $90 million. The congressman asked me to forgive the company’s debt and allow it to choose a new experimental cohort and restart the project. The company’s owners wanted to avoid the financial loss.

- The second came from a rapidly rising star from a Midwestern state. A company in his district operated a Medicare Advantage plan that “got its actuarials wrong.” It was bleeding cash. The congressman asked me to advance the company nearly 6 months’ worth of cash to carry it through to the next benefit year when it could fix its actuarial errors through a redesigned plan. A large and well-funded private equity fund owned the company.

I specifically recall these particular requests because both the congressmen were fierce and vocal proponents of “free markets” in healthcare. Ironically, both sought governmental relief from impacts of operating in free markets. Heads, the company wins. Tails, the company wins. CMS and the taxpayer always lose. That’s rent-seeking at its finest.

Healthcare’s Immense Wealth Transfer

Hypocrisy in politics is as old as rent-seeking. What is particularly striking about these two examples is that they were both market-type arrangements where companies risk capital to generate higher returns. The market should be a harsh mistress when companies underperform (i.e. punishing an ineffective disease management program or inaccurate health plan actuarial assumptions). That enables markets to reward high-performing companies that generate value for customers.

In these cases, the congressmen asked that well-funded companies receive governmental protection from the vicissitudes of the market. The companies and representatives asked me to transfer the tax dollars of working Americans to wealthier Americans whose ideas had failed the market test.

In these cases, the congressmen asked that well-funded companies receive governmental protection from the vicissitudes of the market. The companies and representatives asked me to transfer the tax dollars of working Americans to wealthier Americans whose ideas had failed the market test.

As Case and Deaton argued, these stories illustrate the healthcare system’s bias in favor of the wealthy.

Numerous studies detail how increases in cost of health insurance policies and direct healthcare expenditures consume most or all wage growth for middle income workers. After deducting healthcare costs, lower-income workers have actually suffered losses in adjusted real income. The rising costs they experience have returned no discernable increase in value to them.

Case and Deaton equate the excess healthcare costs to a per capita tax of $8,000[1] per year. In essence, the U.S. healthcare system successfully and efficiently collects a “rent” of $8,000 from all Americans.

Avoiding Counterproductive Healthcare Reform

Case and Deaton conclude their book with some policy recommendations for lifting the veil of despair. For healthcare, they envision a larger role for government in coverage, delivery and payment. It would include compulsory participation, more substantial regulation, and a NICE[2]-like cost and coverage regulator. England as a single payer system uses an unelected administrative body to determine what drugs, devices, and procedures are covered by the National Health System. The body also determines, on a formula basis, what it will pay for them. The authors do note that NICE seems to have resisted lobbying. However, resisting lobbying is not our history, especially regarding concerns of cost and coverage.

The German American economist Henry C. Wallich wrote: “Experience is the name we give to past mistakes, reform that which we give to future ones.” COVID-19 is a global pandemic that has stressed the US healthcare delivery system. The system has shown considerable resilience, but specific weaknesses have become more obvious. “Reform” is inevitable, and the calls for it have begun.

Like Case and Deaton, many policy makers, providers, and academics now demand a more expansive governmental role in healthcare funding and administration. Policy makers must tread carefully. Reform can’t follow the historical path, or it will result in more government intervention and higher “rents.”

As the U.S. healthcare system currently operates, rent-seeking and profiteering is the norm. Without true reform, more government involvement in healthcare means more wealth transfer from the bottom to the top. Income gaps will widen. Despair will increase.

Sources

[1] $8,000 is the difference between the per capita cost of the US system versus the next most costly, Switzerland. Swiss health outcomes are substantially better than those in the US as measured by life expectancy.

[2] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, in the Department of Health in England