October 26, 2016

Value Quest: Capital Formation Challenges for Non-Profit Health Systems

by David W. Johnson, James Moloney and Carsten Beith

There’s a battle outside and it’s ragin’

It’ll soon shake your windows and rattle your walls

For the times they are a-changin’!

Future Nobel laureate Bob Dylan’s 1960s clarion call for new perspective and action applies to healthcare providers as they navigate through the disruption caused by the ascent of value-based payments for healthcare services. The implications for not-for-profit health systems are profound, particularly with respect to capital formation strategies and capital investment policies. As Dylan warned, “he that gets hurt will be he who has stalled….”

Born under the fee-for-service payment environment, traditional approaches to business development, service pricing and capital formation have become calcified for many not-for-profit systems. Limited capital access, excessively conservative capital investment policies and inadequate risk mitigation will hinder performance in the post-reform marketplace. It’s time to “start swimmin’ or you’ll sink like a stone….”

Like the idealists of the 60s, not-for-profit health systems are on an epic quest in a very complicated world. They’re striving to deliver better, affordable and more convenient healthcare services while still adhering to capital formation principles aligned with traditional hospital operating models, growth strategies and mission statements.

As they tackle this quest, many successful systems will adopt powerful “corporate finance-based” capital investment and formation strategies. Corporate finance gives health systems more effective tools and approaches for making the capital investment and financing decisions necessary to transform operations, fuel growth and distribute risk.

Leading not-for-profit health systems will capture and deliver value in post-reform healthcare. More efficient capital utilization will be an integral component of their success.

This commentary discusses the unique operating and governance characteristics of not-for-profit health systems. It details how these characteristics could hamper future competitiveness.

The order is Rapidly fadin’. And the first one now Will later be last For the times they are a-changin’.

Changin’ Times

Despite fundamentally different tax status and governance models, both not-for-profit and investor-owned health systems have prospered under fee-for-service reimbursement. Healthcare’s activity-based payment models have generated significant operating margins to offset losses associated with weak strategies or poor execution.

There will be less room for error in post-reform healthcare. In a more stringent and value-based payment environment, health systems must reduce operating costs to achieve positive margins. This increasingly hostile market environment will challenge the profitability of many well-positioned health systems, regardless of tax status.

Investor-owned health systems generally achieve higher cash-flow margins than not-for-profit systems. They apply that incremental cash-flow to pay taxes and amplify profits. Not-for-profit systems apply incremental cash-flow to fund mission-related activities (e.g. medical education). On balance, not-for-profit systems achieve lower profit margins and operate with higher labor and administrative costs.

Historically, not-for-profit and investor-owned health systems have employed very different approaches to capital formation. Not-for-profit systems rely on pari passu (Latin for equal in all respects) tax-exempt debt, cash accumulation and philanthropy to fund capital investment. Maintaining high ratings is essential for consistent access to debt capital.

In contrast, investor-owned systems have access to equity financing and employ tiered structuring (senior/junior, secured/unsecured) when accessing debt. Strong organizational cash-flow is essential for capital access. Investor-owned systems assess the cost of capital across the spectrum of financing alternatives and select structures that optimize risk-reward tradeoffs.

Post-reform marketplace demands for greater pricing and outcomes transparency are forcing industry consolidation, advancing integrated delivery and exposing under-performing business lines. Incumbent health companies are repositioning. New competitors are emerging. Performance standards are rising.

Increasing performance pressure and greater public scrutiny of their tax-exempt status pose significant challenges for not-for-profit health systems. It’s unclear whether their current operating and governance models are sustainable.

Not-for-profit Health Systems in America

Society establishes not-for-profit organizations for permanence. Think museums, cultural institutions and foundations. Not-for-profit governance models reflect this. They tend to be large, community-based, uncompensated, philanthropically oriented and strategically and financially conservative.

Not-for-profit organizations exist to fulfill a charitable purpose or mission. It’s a historical quirk that charitable healthcare activities center on delivery, not payment. This anomaly reflects healthcare’s early history when health insurance didn’t exist and charitable organizations provided care to those who could not pay.

Society bestows considerable financial benefits upon not-for-profit health companies (no income taxes, no property taxes, access to lower-cost tax-exempt debt and philanthropic support) in exchange for funding some or all of the care costs for indigent patients.

It’s a popular contract: approximately 80% of U.S. hospitals have a not-for-profit or governmental ownership structure. These include the healthcare sector’s leading brands, such as Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, Kaiser Permanente and Mass General. Not-for-profit health companies typically are mission-oriented, care for the medically indigent, train doctors, educate the community and conduct basic research. They are large community-focused employers.

At the same time, not-for-profit health systems must access the public debt markets to fund new capital investments. Health systems’ ability to access the debt markets is a function of their balance-sheet strength, profitability and market position.

Consequently, not-for-profit health systems must operate simultaneously to fulfill charitable obligations and meet competitive market requirements. A short phrase, “no margin, no mission” captures this tension.

Managing conflicts between mission and margin can compromise organizational effectiveness. Too often, not-for-profit health companies are parochial, inefficient and facility-centric.

Operating Constraints Imposed by Not-for-profit Status

Harvard Business School Professor Clay Christensen believes there are no inherent differences between not-for-profit and for-profit healthcare systems. Each provide the same services, operate within the same regulatory scheme and need to generate profits for long-term sustainability. It’s also true that most consumers don’t know whether their local hospital is not-for-profit or for-profit.

Notwithstanding similarities in business models, unique governance and operating characteristics can inhibit the organizational effectiveness of not-for-profit healthcare companies in a number of areas. These include resource allocation, board accountability, major capital programs and ownership change.

- Resource Allocation: Most non-profit health systems experience public criticism when profit margins climb above 5 percent. Demands for charitable services increase and regulators question the need for tax-exempt status. As a result, most non-profit health systems accept constrained profitability and tolerate greater operating inefficiencies.

Labor is a hospital’s largest expense. Payroll costs as a percentage of revenues are significantly higher for non-profit hospitals. Non-profit hospitals also tend to be less efficient at managing supply costs and revenue collection.

Some non-profit proponents claim higher expense levels are necessary to fund mission-related activities. While true at the margins, less efficient operations usually explain most of the performance differential.

- Board Accountability: There are over 3,000 non-profit hospitals in the U.S. They are private Their boards of trustees have minimal accountability to the broader body politic. Non-profit boards tend to be large, voluntary and uncompensated. Often, local business leaders with vested interests in a hospital’s operations serve as part of its governance structure.

Not surprisingly, there is enormous variability in the caliber and capabilities of hospital governing boards. Many, perhaps most, non-profit organizations lack engaged boards that hold management accountable for operational and strategic performance.

Consequently, management exercises disproportionate control over organizational decision-making. This can compromise organizational effectiveness, particularly when managers conflate their individual interests with broader organizational goals.

- Major Capital Programs: Return on investment (ROI) is the lifeblood of for-profit companies. Consistent failure to generate returns on capital investment that exceed the cost of accessing that capital leads to financial distress.

Given their high cost, major capital programs must generate adequate returns to merit investment. By necessity, investor-owned companies must be more attentive to capital investment decisions, projected investment returns and investment risks.

Capital investment is more nuanced in non-profit organizations. While non-profit health companies forecast expected returns, their decision criteria focus more on affordability than projected returns.

A major capital program’s affordability is more a function of balance sheet strength and philanthropic support than projected cash flows. Once deemed affordable, non-profit boards consider qualitative project-approval factors, such as brand perception.

Trustees believe their doctors, researchers and patients deserve state-of-the-art facilities irrespective of whether or not there is sufficient market demand for them or whether returns on invested capital are accretive to the system’s financial strength.

- Ownership Change: Non-profit boards tend to be community-centric and committed to institutional preservation. Local bias poses incremental hurdles for organizations that want to consolidate hospitals.

The currency in non-profit hospital mergers is board seats and managerial positions. There isn’t the clarity between buyer and seller that occurs in for-profit mergers and acquisitions. Strategically-compelling mergers often fail because CEOs can’t agree on who will lead the combined organization.

Cultural and religious factors have disproportionate influence in negotiating agreements. Attachment makes it hard to relinquish control of local institutions even when it is financially and strategically beneficial to do so.

Many trustees believe selling to out-of-town or for-profit buyers violates fiduciary responsibilities. Too often, boards demand reserve powers or super-majority decision-making that compromise organizational effectiveness. The unfortunate conclusion is that non-profit hospital governance makes asset rationalization more difficult to achieve even when companies agree to combine.

Healthcare’s Culture Clash

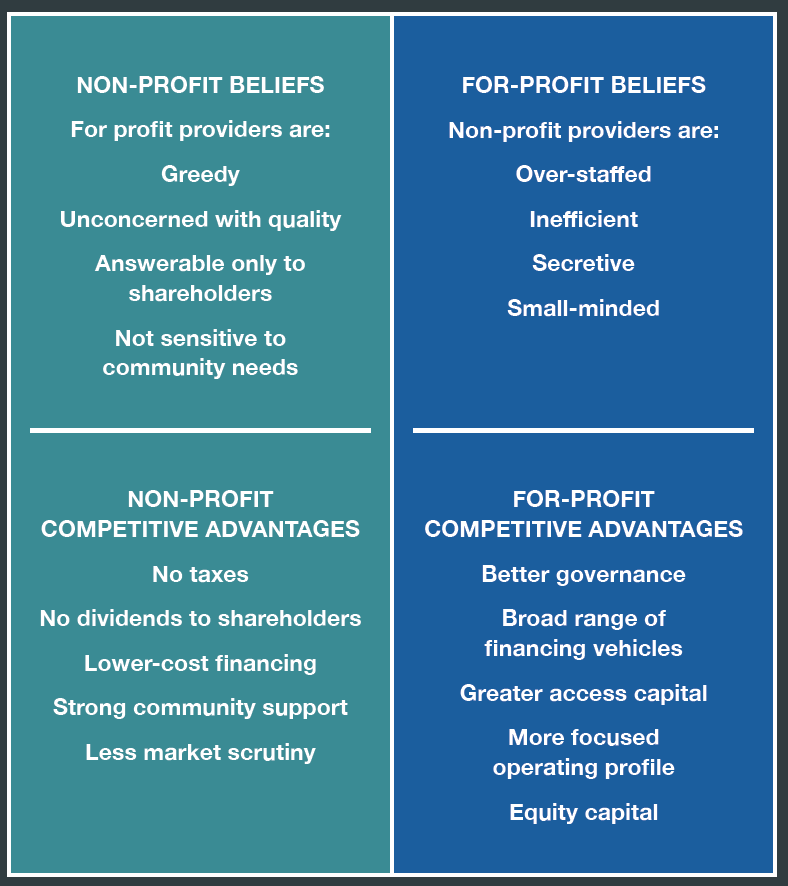

While for-profit and non-profit hospitals provide the same services, they operate with different beliefs. The chart below illustrates their differing worldviews:

Not surprisingly, cultural differences and imbedded mindsets can inhibit organizational flexibility. This is particularly true in not-for-profit organizations that are less accountable to external audiences for their operating performance.

By default, many not-for-profit organizations manage operations to maintain specific investment-grade credit ratings, such as AA/Aa. This requires maintenance of high cash balances and imposes significant opportunity costs by locking up huge sums of capital.

The rationale for maintaining high investment grade ratings increases the probability that the system will have access to capital in difficult markets. While important, it’s unclear whether objective analysis would validate the risk-reward tradeoff. Despite significant market turmoil, virtually all health systems survived the great recession of 2008/09 and have prospered since.

By contrast, investor-owned health systems generally carry non-investment grade ratings. The ability to access both equity and debt markets enables investor-owned systems to execute capital formation programs more efficiently at lower costs. The taxable capital markets incorporate lower risk premiums for non-investment grade borrowers.

This makes debt funding relatively more attractive than equity funding. As a result, it is economically advantageous to use a larger proportion of debt (even with non-investment grade ratings) in a company’s capital structure. Debt funding is lower-cost, highly liquid and tied to organizational cash-flow.

Harsh Post-Reform Market Environment

Increasingly, the ownership structure of not-for-profit and investor-owned health systems is a distinction without a difference. In particular, multiple forces are creating convergence between their capital formation strategies.

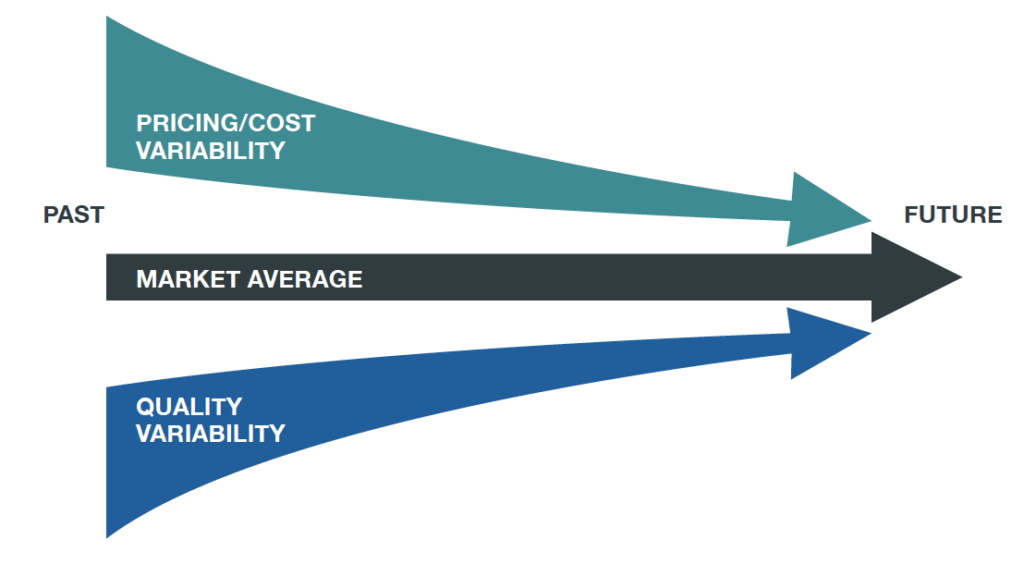

Markets are agnostic and results-driven. Healthcare customers care about quality, costs and outcomes, not organizational mission. Market commoditization in healthcare is creating less performance variation. Given lower profit margins in commodity services, achieving high volume with minimal cost variation is essential to success (see chart below).

Moreover, provider and payer business lines are blurring. As industry consolidation continues and health companies take on more risk, the corporate profiles of not-for-profit health companies increasingly resemble their for-profit counterparts.

In many respects, not-for-profit healthcare’s societal compact is growing more tenuous. In 2013, the highest revenue grossing hospital in the U.S. was a not-for-profit, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), at $11.87 billion[1]. In March 2013, the city of Pittsburgh sued to remove UPMC’s tax-exempt status, alleging the medical center should pay approximately $20 million annually in additional payroll taxes and property taxes[2].

This year, 7 of the 10 most profitable hospitals in the U.S. are not-for-profits and the Illinois Supreme Court will hear a case on whether the Carle Foundation Hospital, one of the most profitable hospitals in the U.S., should pay property taxes[3].

Expect these types of battles to increase as cash-strapped governments seek new revenues, particularly since the number of Americans without health insurance is declining under Obamacare. Not-for-profit health systems may not withstand close legal scrutiny regarding their tax-exempt status in light of their actual activities.

Market Compression and Regulatory Scrutiny

Low interest rates, narrow credit spreads and the relative illiquidity of the smaller tax-exempt debt market are negating the incremental advantages of not-for-profit’s discounted borrowing costs. There is marginal difference between tax-exempt and taxable borrowing costs at equivalent credit rating levels along the yield curve.

Moreover, tax-exempt organizations often sacrifice high-return capital investments in order to preserve a higher credit rating which may shave 25 or 50 basis points off subsequent debt costs. It is the rare not-for-profit board that will approve a one or two notch credit rating downgrade in order to access the capital necessary to pursue high-return strategic opportunities.

Tax-exempt borrowing comes with greater regulatory restrictions, increasingly comprehensive disclosure and higher issuance costs. Tax-exempt funding is also available only for eligible tax-exempt purposes, usually facilities and equipment. Validating that tax-exempt assets support allowable tax-exempt activities over the entire life of the tax-exempt debt can be a time-consuming and expensive enterprise.

The cost-benefit ratio of tax-exempt debt to not-for-profit health companies is clearly increasing. Funding of other strategic investments (such as physician networks, new information systems or risk taking enterprises) must come from balance sheet cash and cash flow from operations. Sustaining balance sheet strength with these new demands for cash can be daunting for most tax-exempt hospitals.

The traditional strategies for capital formation employed by not-for-profit health systems cannot accommodate the market’s increasing performance-based, outcomes-driven business models. Post-reform healthcare requires more rigor regarding the sustainability and potential of system assets (particularly facilities) and business lines.

To excel in this new environment, not-for-profit health systems will need to make tougher resource allocation decisions, adopt more flexible funding approaches, adhere more closely to standard ROI metrics, and leverage more expansive strategic partnerships by determining which business lines they should own, outsource or share.

Survival of the Most Adaptable

The future belongs to health systems that can adapt to new market realities. This requires not-for-profit health systems to play offense. They must become proactive in assessing their relative competitiveness, managing strategic risk and funding investments.

In consumer-driven healthcare, health companies will provide care where and how customers want to receive it. Operating in this “retail” paradigm requires not-for-profit health systems to rethink market positioning, strategic alliances, capital formation and governance. Sustainability requires making the right strategic and resource allocation decisions along with superior execution.

Let’s leave the last word to the father of evolution, Charles Darwin. He observed,

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most adaptable to change.

What is true in nature is also true in business. Adapting to dynamic market circumstances differentiates winning companies, particularly during periods of industry disruption when the “times they are a-changin’.”

In post-reform healthcare, it is essential to remember that outcomes matter, customers count and value rules.

[1] Molly Gamble, “100 Top-Grossing Hospitals in America,” Becker’s Hospital Review, June 24, 2013

[2] Elizabeth Rosenthal, “Benefits Questioned in Tax Breaks for Non-profit Hospitals,” AIP website, December 16, 2013, http://aid-us.org/benefits-questioned-in-tax-breaks-for-non-profit-hospitals

[3] Carla K. Johnson, “Study: 7 of 10 most profitable US hospitals are non-profits,” AP Big Story, May 2, 2016, http://bigstory.ap.org/article/8867beb032c049378e4a83d150cb8bc3/study-7-10-most-profitable-us-hospitals-are-nonprofits

CARSTEN BEITH

Carsten Beith joined Cain Brothers in 1993 to open the firm’s Chicago office. Mr. Beith is the Head of Cain Brothers’ Health Systems Group and a member of the Firm’s Executive committee. With over 22 years’ experience, his engagements have encompassed a broad range of transactions covering hospitals and health systems, academic medical centers, physician groups, managed care organizations, and other health care service providers.

Carsten Beith joined Cain Brothers in 1993 to open the firm’s Chicago office. Mr. Beith is the Head of Cain Brothers’ Health Systems Group and a member of the Firm’s Executive committee. With over 22 years’ experience, his engagements have encompassed a broad range of transactions covering hospitals and health systems, academic medical centers, physician groups, managed care organizations, and other health care service providers.

Cain Brothers is a pre-eminent investment bank focused exclusively on healthcare. Our deep knowledge of the industry enables us to provide unique perspectives to our clients and is matched with the knowhow needed to efficiently execute the most complex transactions of all sizes.www.cainbrothers.com

JAMES MOLONEY

Jim Moloney is Co-Head of the Firm’s Mergers and Acquisitions Advisory practice. Mr. Moloney joined Cain Brothers has over 25 years’ experience in mergers, acquisitions, financings, and real estate transactions. Mr. Moloney is a member of the Firm’s Executive Committee.

Jim Moloney is Co-Head of the Firm’s Mergers and Acquisitions Advisory practice. Mr. Moloney joined Cain Brothers has over 25 years’ experience in mergers, acquisitions, financings, and real estate transactions. Mr. Moloney is a member of the Firm’s Executive Committee.

Cain Brothers is a pre-eminent investment bank focused exclusively on healthcare. Our deep knowledge of the industry enables us to provide unique perspectives to our clients and is matched with the knowhow needed to efficiently execute the most complex transactions of all sizes.www.cainbrothers.com