October 9, 2024

Why Bother Even Trying to Lower Consumer Drug Prices?

I worked with a reporter years ago whose writing style was so complex structurally that his stories were nearly impossible to edit. Not that his stories didn’t need editing. All reporters need a good copy editor to make their copy better. It’s just that his writing was so complicated, trying to do even just a light edit would risk introducing errors or topple his version of an inverted pyramid to the ground.

Changing a word or phrase or sentence in one part of his article could change the meaning of a word or phrase or sentence in another part of his article despite being many column inches away from the thing that you wanted to change in the first place.

We called his writing style Jenga, after the game of wooden blocks. I have no doubt that he wrote that way deliberately so no one would touch his copy. And we rarely did. His stories were incomprehensible but apparently never inaccurate as we never had to correct them after publication.

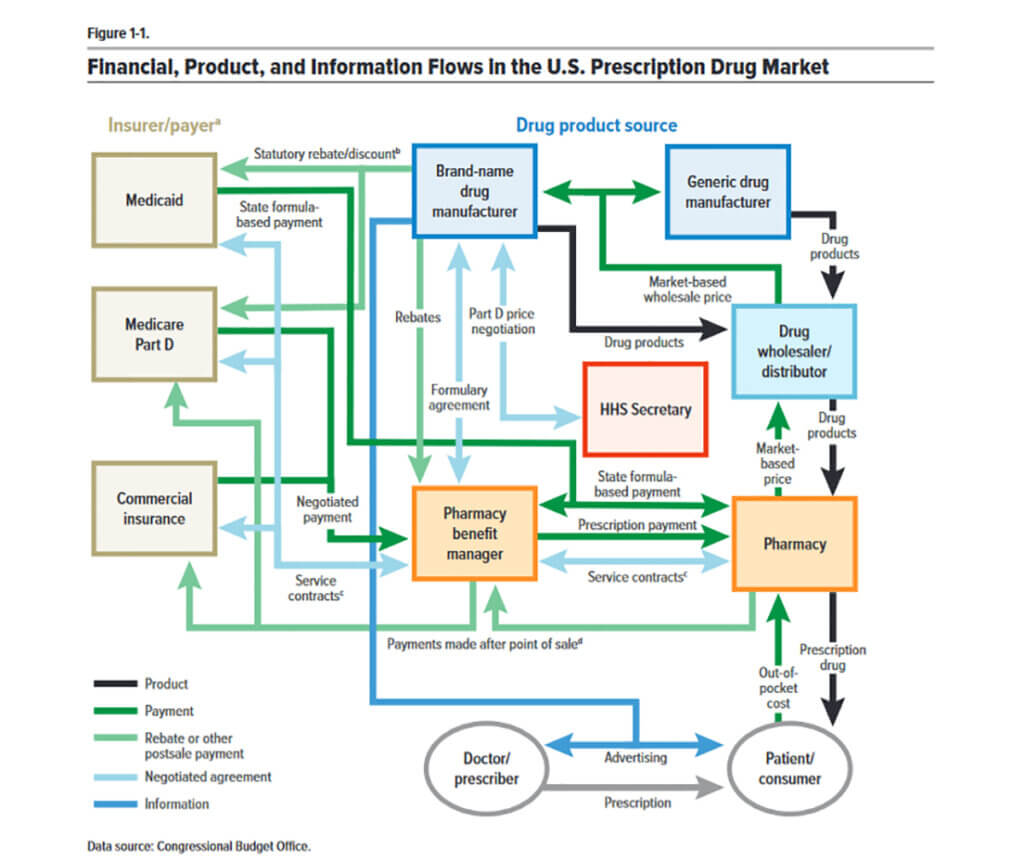

What does that trip down journalism lane have to do with reducing drug prices? It’s a good analogy of how we set prescription drug prices in the U.S. Opaque doesn’t begin to describe business relationships, contract terms and levels of integration among pharmaceutical manufacturers, drug distributors, group purchasing organizations, health insurance companies, pharmacy benefit managers and pharmacies that somehow result in prices that consumers pay for their medications. The system is nearly impossible to change for fear of making it worse for consumers.

A new report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) drove that point home to me in a big way. So big it gave me that journalism flashback. The 46-page CBO report looks at seven policy options to lower the average prices that consumers pay for drugs in retail settings. In the CBO’s scenario, the policies would take effect in 2025, and the price change would be in 2031, or six years after the policy took effect.

I won’t bore you with the analysis. I’ll just skip to the good part. Here are the seven policy scenarios and how they would reduce drug prices in ranked order:

- Set maximum allowed prices based on prices outside of the U.S. (greater than a 5% reduction).

- Require manufacturers to pay inflation rebates for sales in the commercial market (1% to 3% reduction).

- Expand the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program (0.1% to 3% reduction).

- Allow commercial importation of prescription drugs distributed outside of the U.S. (0.1% to 1% reduction).

- Eliminate or limit direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertising (0.1% to 1% reduction).

- Facilitate earlier market entry for generic and biosimilar drugs (0.1% to 1% reduction).

- Increase transparency in brand-name drug prices (0.1% reduction to a slight increase).

Absent setting drug prices based on drug prices in other countries, none of the policy approaches really take a bite out of consumer drug prices after six years. Seems like a lot of investment of time and energy not to mention laws and regulations for not much return. Or even making things worse.

The question is why? The answer to me is on page 11 of the report. Below is the CBO’s flowchart of the U.S. drug market. It’s virtually impenetrable.

Looks like a sentence diagram from someone I know.

Thanks for reading.