October 29, 2019

Will Misuse of Antibiotics Respond to Regulation?

I got my flu shot on Oct. 21. (I’ll let you know how it worked out.) As I waited for my turn at our nearby immediate-care center, I explained to my youngest son, who was there with me to get his flu shot, why our health plan pays 100 percent of the cost of the vaccination and we pay nothing out of pocket.

As his eyes glazed over and quickly returned to messages on his phone, I told him it’s not because our health plan really cares if we get sick. Our plan pays because paying for a flu shot is way cheaper than paying for a trip to the emergency room when you think you’re dying from the flu or for a long stay in the hospital because you have the influenza virus or viral pneumonia.

Deluding myself into thinking he cared and was listening, I launched into a lecture about the difference between viruses and bacteria and why vaccines work on viruses, not bacteria, and why antibiotics work on bacteria, not viruses. If you want your 16-year-old to jump from a waiting room to an exam room the second a nurse practitioner calls his or her name, I’ll give you my lecture notes.

His quickness and our health plan’s actuarial prowess surely swirled together in my brain, and I asked myself: Why is it taking the healthcare industry so long to get this antibiotic stewardship thing right?

To me, it’s a test of which is more effective—regulation or competition—in getting prescribers to do what they know is the right thing for patients now and for patients in the future.

APIC, the trade group that represents infection control specialists, defines antibiotic stewardship as “a coordinated program that promotes the appropriate use of antimicrobials (including antibiotics), improves patient outcomes, reduces microbial resistance, and decreases the spread of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. “

Further, “Misuse and overuse of antimicrobials is one of the world’s most pressing public health problems. Infectious organisms adapt to the antimicrobials designed to kill them, making the drugs ineffective. People infected with antimicrobial-resistant organisms are more likely to have longer, more expensive hospital stays, and may be more likely to die as a result of an infection,” APIC says.

In short, don’t prescribe antibiotics when patients don’t need them, and prescribe only the antibiotic that treats the specific infection. If we don’t do those two things, we’ll all be in bad shape. So, yeah, it’s a big deal.

Education, regulation and self-regulation

And because it’s a big deal, thoughtful people in the private sector and in the public sector are trying to address the problem through education, self-regulation and regulation. Here are a few examples:

- In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published its 24-page Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. The CDC put out a similar 21-page report for nursing homes in 2015 and a 33-page report for ambulatory-care settings in 2016. File these under education.

- Also in 2014, the American Hospital Association released its Antimicrobial Stewardship Toolkit. It’s a six-page document that links hospitals and health systems, clinicians and patients to all kinds of resources regarding the appropriate use of antibiotics. File that under self-regulation.

- In 2016, the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America published a detailed, 27-page set of guidelines for implementing an effective antibiotic stewardship program at any care site, including hospitals and nursing homes. Also file that under self-regulation.

- In 2017, the Joint Commission put into effect a new antimicrobial stewardship standard for accredited hospitals, critical access hospitals and nursing homes. The standard requires facilities to educate “practitioners, staff, and patients on the antimicrobial program, which may (emphasis mine) include information about resistance and optimal prescribing.” A similar standard for accredited ambulatory-care facilities will take effect on Jan. 1, 2020. Put this in the self-regulation file, too. Though it may seem mandatory, accreditation actually is voluntary.

- In 2019, CMS incorporated appropriate antibiotic prescribing into a number of different quality measures that it used to reimbursement physicians under CMS’ Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS. If you scan through this list of 268 MIPS quality measures, you’ll see things like avoiding the inappropriate use of antibiotics for children with ear infections and overuse of antibiotics for adults with sinus infections. File this under regulation.

- In September, CMS published a 103-page set of final regulations in the Federal Register that does a lot of things, including amending Medicare’s Conditions of Participation for hospitals and critical access hospitals. Effective March 30, 2020, hospitals and CAHs will have to have “active” infection control and antibiotic stewardship programs in place if they want to treat Medicare patients. File that under regulation.

Medical experts are telling antibiotic prescribers what to do and why to do it. Industry trade groups are telling members what to do so regulators don’t step in. Regulators are telling antibiotic prescribers what to do and what will happen to them if they don’t.

Influencing prescribing practices

So what’s the net effect of all this interest pouring down on prescribers from three different directions?

In August, the CDC released a 24-page 2018 update to its 40-page 2017 report, Antibiotic Use in the United States: Progress and Opportunities.

If you’re a glass-half-full kind of person, here’s the good news: The number of hospitals with antibiotic stewardship programs “almost doubled” between 2014 and 2017. The agency said 3,816 hospitals had programs in place in 2017.

But if you’re a glass-half-empty kind of person, here’s the bad news: More hospitals launched antibiotic stewardship programs because they had to if they wanted to keep their accreditation. “This increase is likely driven by a number of factors, including new accreditation requirements,” the CDC said.

Behold the power of the Joint Commission to force hospitals to make structural and process changes to comply with new accreditation standards.

Structure and process don’t always result in better outcomes. To wit, the CDC said it’s “working with accreditation organizations to improve assessment of the quality of antibiotic stewardship programs.” In-other-words, the CDC wants to know if the hospitals are serious and the programs are working and hospitals are not just going through the motions to earn their accreditation stripes.

The CDC said 30 percent of antibiotics prescribed in physician offices and hospital emergency rooms in 2016 were unnecessary.

Also in the report, the CDC cited several peer-reviewed studies that show that inappropriate use of antibiotics is an ongoing problem. Like the one that said urgent-care centers were the biggest offenders compared with ERs, physician offices and retail health clinics. (We wrote about that one in “An Urgent Message for Those Who Want Care on Demand” on 4sighthealth.com.)

Or this study in the Annals of Internal Medicine, which came out too late to be included in the CDC report. Researchers from the University of Michigan found that more than two-thirds of nearly 6,500 patients treated at 43 Michigan hospitals for pneumonia got “excessive antibiotic therapy.”

Time to try something different

What this all demonstrates is that prescribing behaviors by providers run deep. Almost as if they’re part of a clinician’s DNA. The general practitioner I went to as a kid in the 1960s and 1970s routinely gave me a shot of penicillin and a box of tetracycline pills no matter what I saw him for. You can find traces of his behavior in many doctors today. And, let’s face it, there are a lot of patients old and young who expect their doctors to prescribe them antibiotics for whatever hurts during cold and flu season. They will find the setting that meets their expectation for treatment.

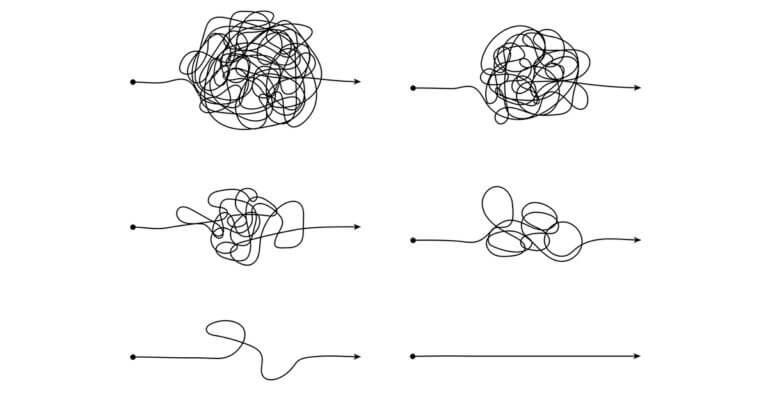

Education, self-regulation and regulation are breaking prescribers of their antibiotic prescribing habits albeit reluctantly and slowly. But how much faster will a horse run if you keep whipping it?

Maybe it’s time to try something else? Maybe something like market-based competition?

Health plans know who prescribes which medications for what diagnoses. Maybe health plans should pay providers more when they prescribe antibiotics appropriately? Maybe they should pay providers less or not at all when they use antibiotics inappropriately? Maybe they should incentivize patients to see providers who adhere to the principles of effective antibiotic stewardship?

Healthcare is a business like any other business. If you want to change behaviors, create an economic incentive to do so. That’s why my health plan doesn’t make me pay for a flu shot. It’s good business.

Thanks for reading.